Two years of contributions to conda-forge: work done during our CZI EOSS 5 grant

Published February 10, 2025

jaimergp

Jaime Rodríguez-Guerra

In late 2022, CZI awarded us three EOSS grants. One of them was a two-year proposal under the name "Transparent, open & sustainable infrastructure for conda-forge and bioconda". The proposal, co-submitted by Quansight Labs and QuantStack, had three main focus areas: maintaining and improving infrastructure, creating a new maintainer's dashboard, and implementing OCI-based mirroring for the packages. This work has now concluded, and we would like to publish a summary of what we have achieved!

What are conda, conda-forge and bioconda?

The conda ecosystem provides unified open source tools and specifications to build and distribute precompiled packages for software projects across different operating systems, architectures, and programming languages. Its unique position in data science, research, and scientific software engineering is a testament to its capabilities, particularly in scenarios where different programming languages and platforms are often used together to tackle complex multidisciplinary challenges.

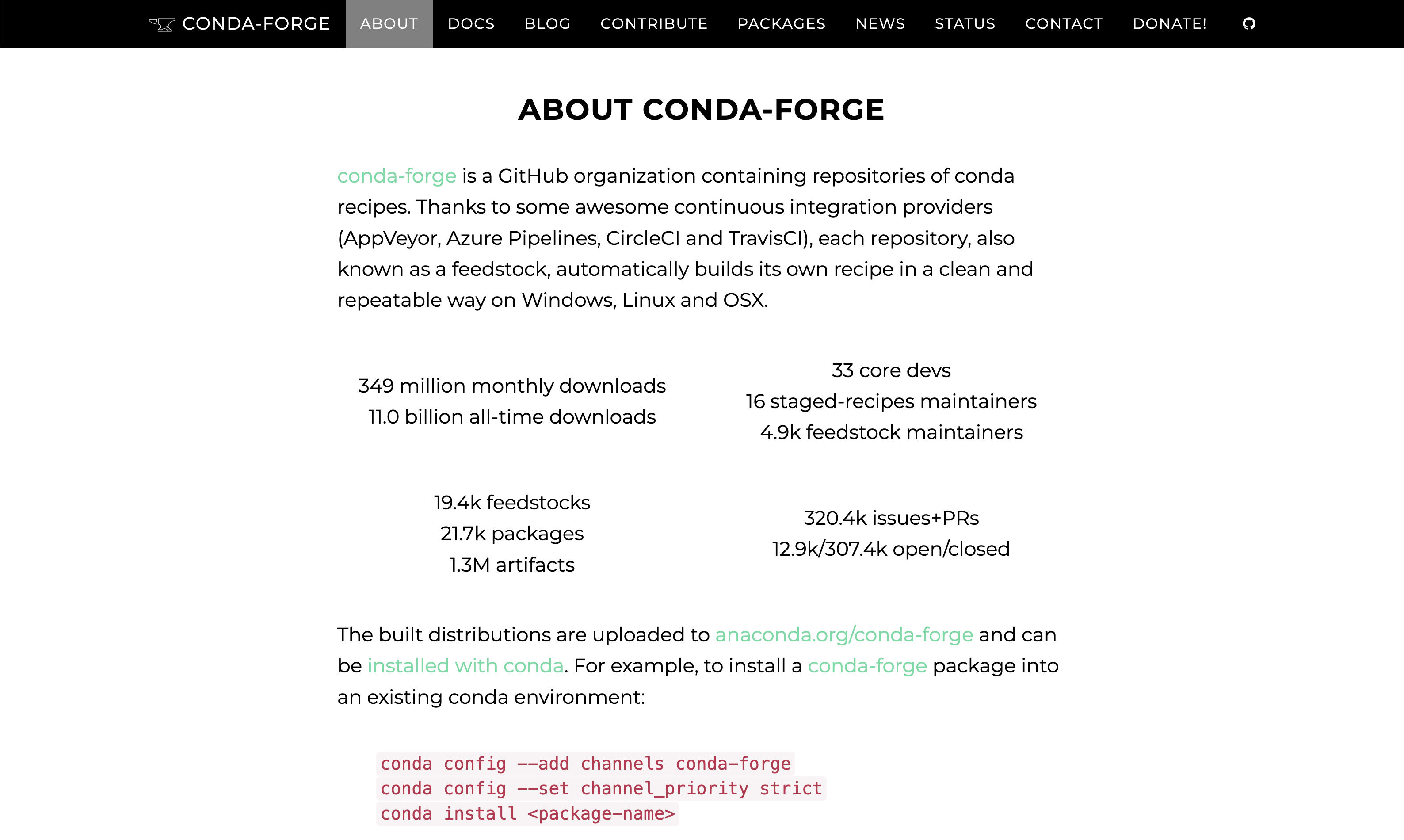

The conda ecosystem includes various community-driven projects, like the Bioconda and conda-forge build farms. These are collective efforts to maintain an increasingly large collection of conda recipes and automation infrastructure. Both were founded in 2015 in response to scientific software users' frustrations when attempting to install system package dependencies. While conda-forge is a general-purpose channel, Bioconda extends conda-forge to cater to the computational biology field needs, as explained in their Nature publication.

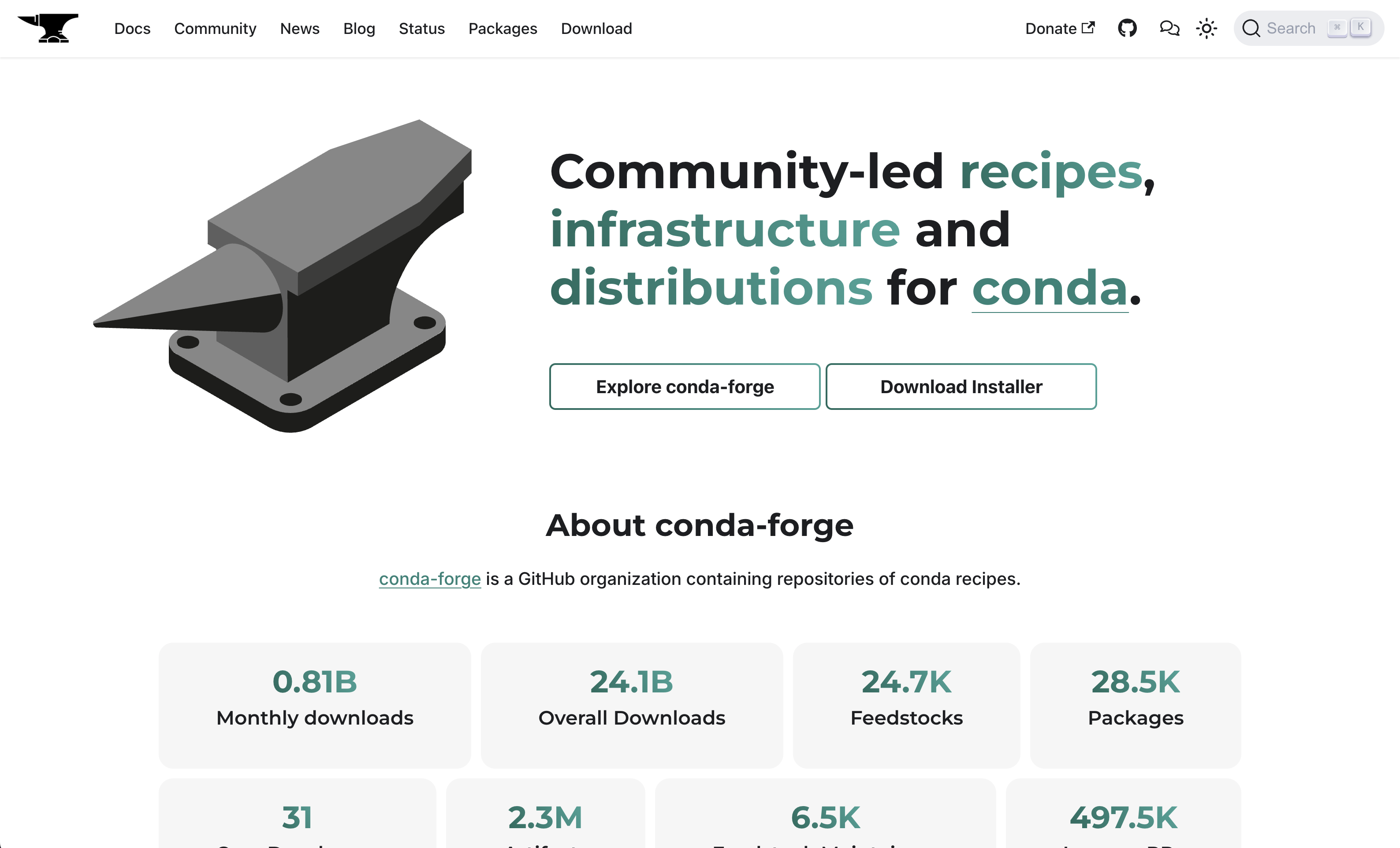

The emergence of these communities massively reduced the scientific packaging toil by building on transparency, automation, compatibility, and open-source principles. As a result, they have grown exponentially, as has the number of artifacts hosted and downloaded: conda-forge alone serves 2M+ artifacts, downloaded 800M+ every month.

Ten years later, such exponential growth has significantly increased the pressure on its underlying infrastructure, tooling, and maintainers' workflow for both communities.

The proposal

The full proposal can be found in the Funding section of the conda-forge.org website. The work was scoped in three areas. Quoting our announcement blog post:

1. Reducing infrastructure technical debt

Conda-forge and Bioconda rely on infrastructure and tooling distributed across many GitHub repositories, external CI services, Heroku "dynos" and AWS instances. Many were built as ad-hoc fixes and currently lack documentation or risk mitigation plans. We plan to migrate the configuration and infrastructure provisioning to reproducible, vendor-agnostic tools such as Terraform, complemented with rigorous testing, vulnerability detection, and documentation strategies to enable better security, reliability, and recovery from adverse events.

2. Adopting an OCI-based mirroring strategy

Anaconda.org is the default and sole host for all published and installable scientific packages. Adopting vendor-neutral tooling and standards (such as OCI, the Open Container Initiative) will ensure we uphold the core principles of open source and aid the project's long-term sustainability. We also believe that using and building an infrastructure that follows these open principles are the right foundation for more productive and impactful research and education.

3. Development of a maintenance dashboard on Quetz

There is no straightforward way to monitor the operational status of conda-forge or Bioconda's infrastructure. The existing conda-forge.org/status panel is far from giving a comprehensive view of ongoing maintenance tasks, bottlenecks or the overall health of the many bots and infrastructure pieces. Having a detailed picture of the infrastructure and automation tools will significantly improve the maintainers' workflow and aid with identifying critical risks. The dashboard will be built on top of Quetz, an open source server for hosting conda packages, allowing for increased transparency and extensibility.

Over these two years, the Quansight and QuantStack teams involved the following people:

- Quansight: Tania Allard, Jaime Rodríguez-Guerra, Vinicius Cerutti, Amit Kumar, Gonzalo Peña-Castellanos, Isabela Presedo-Floyd, Axel Obermeier, Isuru Fernando, Sophia Castellarin.

- QuantStack: Sylvain Corlay, Gabriela Vives, Hind Montassif, Johan Mabille, Afshin Darian, Florence Haudin, Vanessa Sochat.

The proposal was scoped so that QuantStack team would lead the OCI mirroring efforts, while the Quansight team would tackle the infrastructure details. The maintenance dashboard and website improvements would be split roughly 50-50 between the two teams.

As we started working on this project, we realized there were many synergies from other funding sources that could be aligned together for maximum output. So in the next few sections you will also learn about other initiatives that ended up scoped together, like the new website or the GPU CI server.

Website and maintenance dashboard revamp

The conda-forge.org website used to be built around its Sphinx documentation, with several add-ons coming in from different repositories that ended up being "mounted" on the main conda-forge.org deployment. While functional, this approach made the site difficult to maintain and led to many inconsistencies in design, usability, and contribution workflows.

cloud-sptheme design.

conda-forge/status.

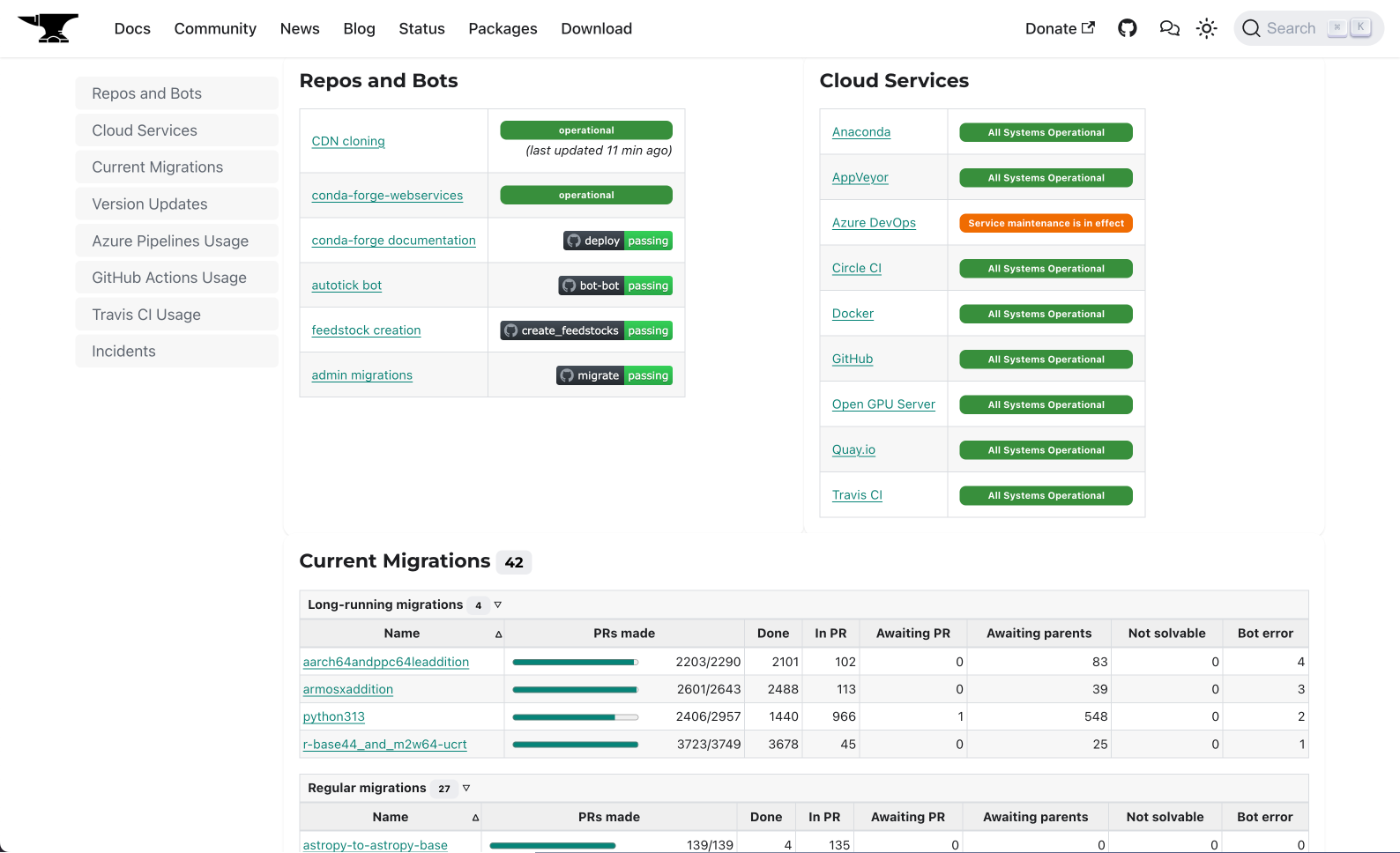

One of those add-ons was the /status page, which consisted on a periodically regenerated static HTML document templated with Jinja. The idea was to rewrite this page with modern web components, like a React app that could fetch the necessary data on demand, live, without having to resort to cronjob-driven regeneration.

In parallel, we were trying to write some documentation for the infrastructure details we were discovering as part of our discovery and research tasks. After all, one of the problems we had detected is that the existing documentation was too scarce and out of date. Maybe because the contribution workflow in the old conda-forge website was very clunky. Specially in comparison to what we had observed in other projects that were using Docusaurus. Our hunch was that if we smoothened the contribution frictions, maybe more folks would be inclined to help maintain the documentation.

We decided to start a prototype website based on Docusaurus just to see how it felt to write for this platform, and... the writing experience was too good to ignore. Live reload just works and it is instantaneous. Docusaurus would not only allow us to write a React app for the status page. It would also enable refactors in all those other Sphinx add-ons, like the blog or the announcements page and RSS feed. Instead of having many loosely coupled repositories, we could have one website built from one place...

So we went for it!

We were lucky to have Asmit Malakannawar join us for a Google Summer of Code internship in conda-forge during the summer of 2023. He was in charge of designing a new, modern frontpage for the Docusaurus site. You can read more about this experience in Asmit's website. Together with Tania Allard and Isabela Presedo-Floyd (Quansight), as well as Gabriela Vives (QuantStack), we ensured that the new design and color system complied to essential accessibility affordances.

Shortly after, Afshin Darian (QuantStack) started building the new status page (conda-forge.github.io#2090). We had decided to not rely on a Quetz instance because that would tie us to running and maintaining a server 24/7, with the associated costs. Instead, the new proposal presented a client-side dashboard built with components already offered by the Docusaurus framework. Since it uses React, it was deemed as a good compromise of complexity and long-term maintenance costs (specially for the conda-forge teams, who are not too familiar with the fast changing frontend development). After lots of feedback (118 comments!), the main PR was finally merged in March 2024.

As we were increasingly satisfied with the results Docusaurus was offering, we started consulting the conda-forge community and submitted the final website redesign proposal for review and merge. However, we were still serving the documentation itself from Sphinx. It took a couple of extra PRs to convert Sphinx's RST text to Docusaurus' Markdown and make it look great. Klaus Zimmermann (Quansight) also contributed new consolidated documentation taken from our infrastructure notes.

The website was officially launched on April 9th, 2024. The announcement blogpost contains some more details if you are curious, but the main changes are:

- Accessibility-aware theme with dark and light modes.

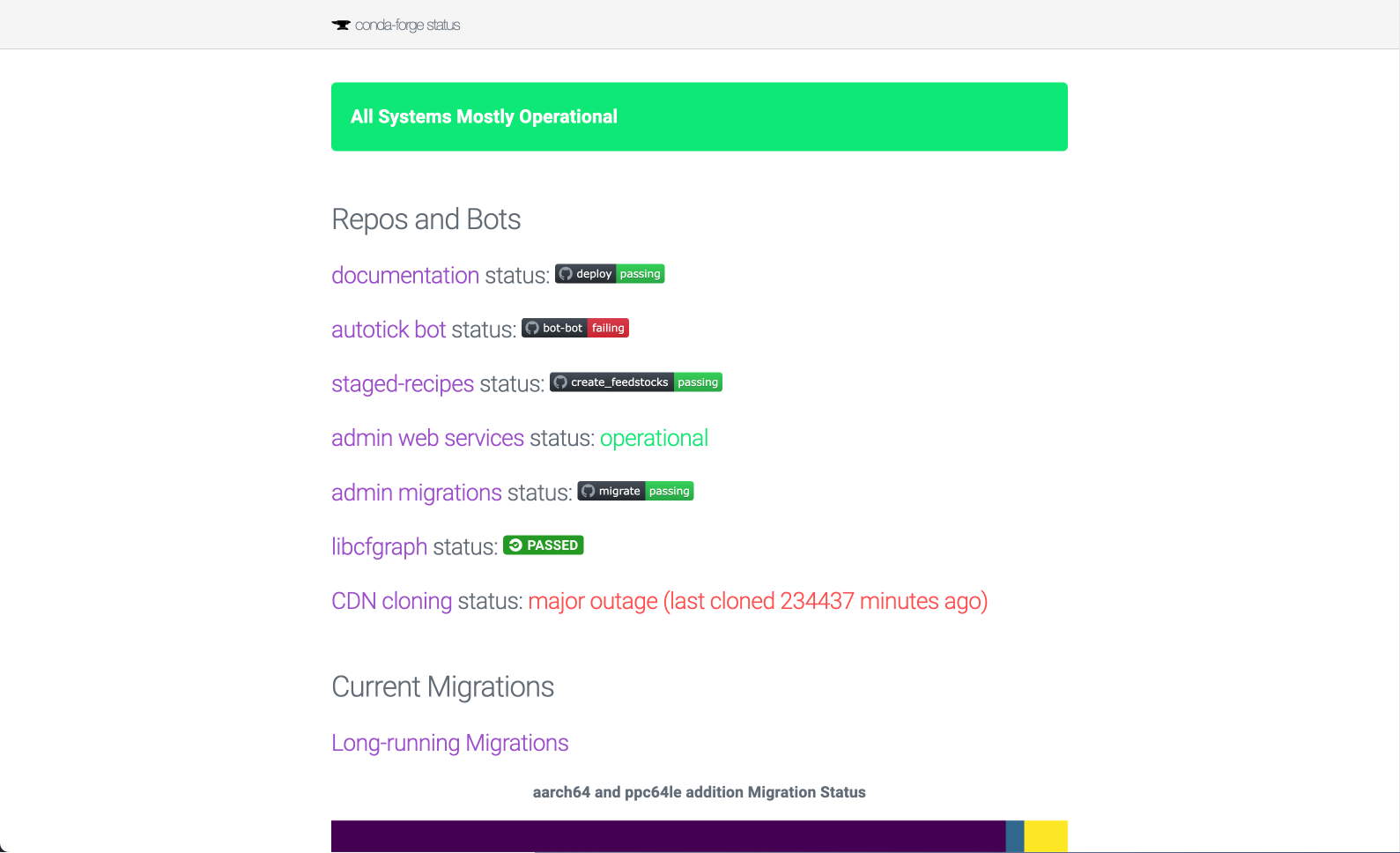

- The React-based

/statuspage monitors different parts of our infrastructure and services and reports their usage. It also informs of the progress of current and past migrations and version updates. If there's an incident, it syncs with theconda-forge/statusissue tracker and report ongoing problems. All data is fetched live from different JSON endpoints so there's no cronjob regeneration needed. - The search feature is backed by Algolia, which allows readers to find content more accurately.

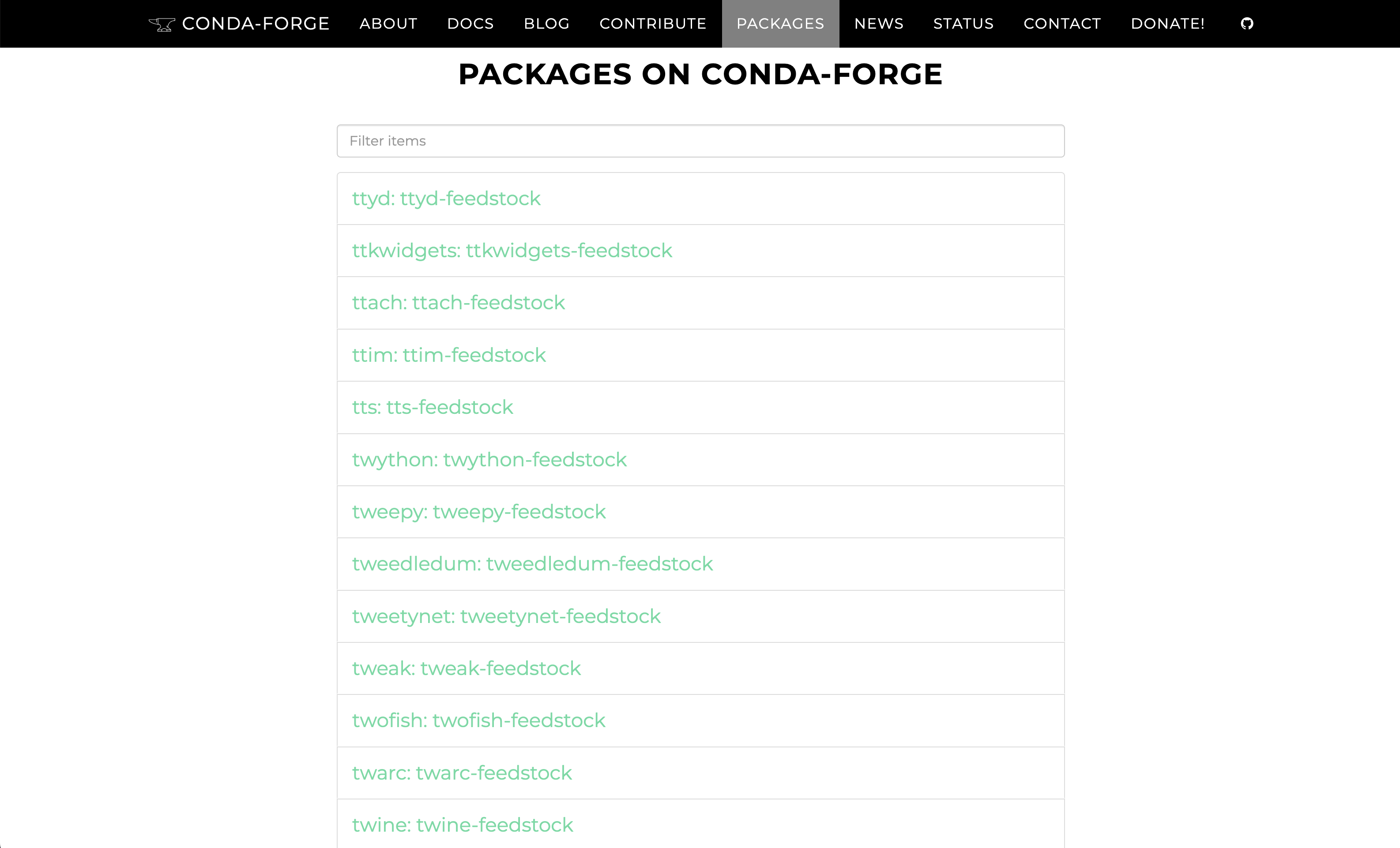

- The

/packagespage lists all packages and their feedstocks, with a fast search.

Fun fact: the decision to use Docusaurus for the conda-forge website inspired the conda.org maintainers to use it too!

OCI mirroring

The channel-mirrors Github organization hosts experimental mirrors of conda-forge and bioconda using Github Packages. The goal for this item was to finalize the prototype and implement the client-side tooling required to use registries that implement the Open Container Initiative (OCI) Distribution specification.

This task was assigned to the QuantStack team. As part of the mamba 2.0 refactor, they added compatibility for a general notion of mirrors and also OCI support. They also co-authored the corresponding CEP to standardize the design across the whole ecosystem.

During the review process, several shortcomings were identified in the original design of the mirroring system. For example, container names can't start with an underscore _, but some conda packages use this character to denote the "private" character of a package, à la Python. This needs to be mapped cleanly to avoid accidental name clobbering. Same with version strings that use + signs and others.

After careful deliberation, it was decided that the CEP in its current form wouldn't be accepted unless the name mapping design is revised. Once that happens, the CEP will be adjusted accordingly and then a new vote will be called.

In the meantime, the OCI mirror is still functional as a backup. Users can browse the resulting containers via the Github UI and its layered storage powers some infrastructure elements we built as part of the grant (more on this below).

You can even use it to solve and install some environments! As mentioned before, this works right away with mamba v2. You can use the oci:// protocol in your channels to indicate this. You can find more details on the mamba 2.0 release announcement.

If you are using conda, you can run a local copy of this OCI middleware layer we wrote: conda-oci-forwarder. It's a small FastAPI application that serves the regular conda channel HTTP API, but negotiates the necessary calls to forward the requests to GHCR's (GitHub Container Registry) channels-mirrors in the backend. However, it doesn't map conflicting characters well, so you have to be lucky that the packages you included do not use any of those.

Infrastructure improvements

10 years of organically grown infrastructure are plenty to go through several rounds of maintainers, institutional knowledge gaps and heaps of technical debt. This can happen in any resource-constrained open source project. Though conda-forge's set of constraints differs from those of many other projects in the scientific computing and packaging and distribution ecosystems.

conda-forge is not just one more open-source project. The main deliverable is not a tarball of code the maintainers release so it is consumed by authors and/or users. In that kind of project, the responsibilities of the maintainer are centered on the project and tending to its own development roadmap, fixing issues, fostering a community of contributors...

In conda-forge, the main output is a service. Particularly, a package building service supported by an ever-evolving infrastructure constructed around interchangeable free or ultra-low-cost resources. This service is expected to operate 24/7 so it needs to be as robust as possible, without incurring large maintenance costs, both in monetary and human resourcing terms. No one wants to be on call in case "a server dies" or be responsible for a large bill if a bad actor abused the CI. This set of constraints is very unique and limits what type of infrastructure changes can be done in a grant like this. If you were thinking of AWS this, Kubernetes that... wrong direction!

Documenting the infrastructure

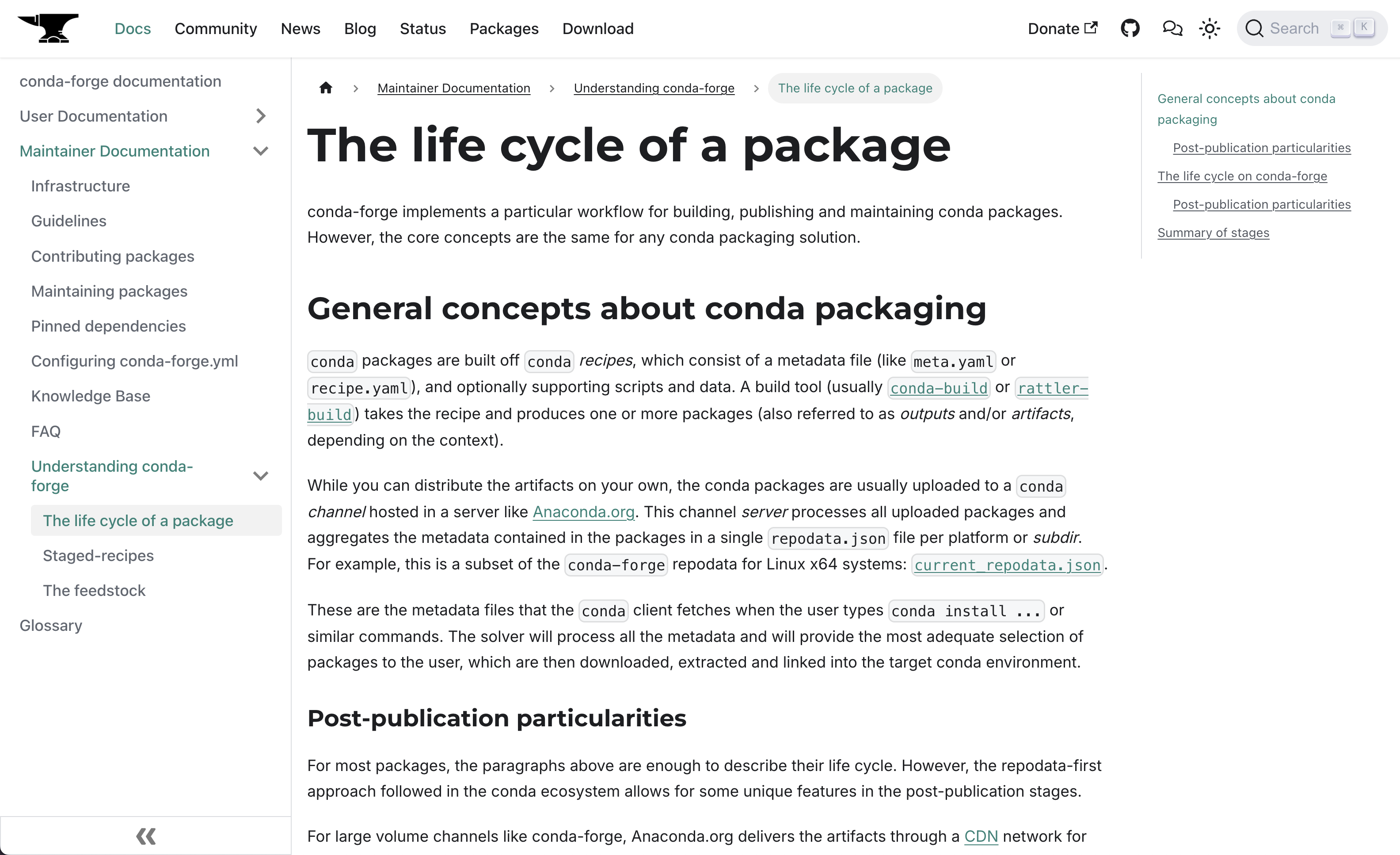

Now, what can we do then? Our first item was to audit our own infrastructure to make sure we had a complete inventory of its components and interactions, and then document it for the community. We partially followed the PASTA process, a threat modeling methodology that consists of seven steps, of which the first three focus on completing a system's inventory. Perfect! The useful parts of this investigation were aggregated in these new sections of the conda-forge website: Infrastructure and Understanding conda-forge. Thanks to Vinicius and Klaus for their work!

One problem with centralized documentation is that its contents tend to drift away from their original sources, unless they are automated in some way. This was the case with the section for the main configuration file of every feedstock: conda-forge.yml. The structure of this file is mostly governed by code in conda-smithy. We implemented a self-documenting JSON schema built with Pydantic, and then created a custom React component to fetch and render the schema in Docusaurus on every visit. The result can be checked in Configuring conda-forge.yml. Having a JSON schema also allowed us to validate its content with the conda-forge linter bot. Two birds, one stone! Thanks to Vinicius and Isuru for their help pushing this through the finish line.

Better practices for security

During the PASTA assessment we identified the need for better token management practices. We have started using Pulumi and 1Password to centralize our secrets handling in a single platform via the newly created conda-forge/infrastructure repository. Both Pulumi and 1Password are generously sponsoring conda-forge via their open source plans. Thanks to Sophia for her work setting this up!

During this time, members of the core team also pointed out that many of conda-forge's Github Actions workflows were using flexible version pinning, and that it would be safer to use strict commit pinning paired with automated Dependabot pinnings. After tens of PRs, all of our repositories default now to this practice.

We also formalized our security policy so users know how to report a security incident and what to expect from our response.

Package metadata discovery

The infrastucture inventory helped us discover several pieces that required our attention. One of them was the regro/libcfgraph repository which hosted 1M+ JSON payloads extracted from every artifact ever published in conda-forge. This repository was so massive that it was flagged by GitHub Support, who kindly asked us to shut it down; we weren't even been able to clone it in GitHub Actions anymore and had to resort to Circle CI which, for some reason, was able to fetch a shallow copy in... "just" 20-30 minutes!

libcfgraph's directory structure provided stable URLs to the metadata of every artifact (e.g. check this one for conda 22.11.0), which was really useful to debug recipe build failures related to missing or conflicting dependencies. If we had to shut it down, we needed a replacement!

Our involvement in the OCI mirroring work made us realize that, since the info/ metadata directory was available as its own separate layer, we could query it directly without downloading the whole artifact (imagine downloading the full cudatoolkit package just to query a few KBs of JSON). We took on this idea and added OCI support to the conda-forge-metadata package in 0.4.0. With that piece in place, we started a Streamlit app that lists every artifact in conda-forge and queries its metadata from the OCI mirror on demand. We then learned that conda-package-streaming also allows querying the info/ subpackage of .conda artifacts stored in the Anaconda.org CDN. The final strategy was to use conda-package-streaming for .conda artifacts and the OCI mirror for the older .tar.bz2 artifacts.

The end result was published to conda-metadata-app.streamlit.app, and has since received several updates. Among them, a search function to find which artifacts provide a given file path. For example, if you want to find out which package provides libcuda.so and then put it in your recipe. This is supported by conda-forge-paths, a database we built on top of the initial libcfgraph repository, and then extended with the same streaming support we are using in the Streamlit app. This database lists every path ever published in a conda-forge artifact, and maps it to the provider package(s). Ah, and you can use it locally with datasette! In the future, this database would also allow us to run cross-clobbering checks between packages, at build time.

libcfgraph was also used by the conda-forge's bots to fetch information about the run_exports field of some packages. We decided to submit a Conda Enhancement Proposal (CEP) to the conda Steering Council so this information was served alongside the repodata.json files in each conda channel. The proposal was formalised and approved as CEP 12: Serving run_exports metadata in conda channels. We then contributed the necessary functions to conda-forge-metadata so this file can be used by the conda-forge infrastructure.

GPU CI, faster provisioning and more complete logs

During this time, we had also applied for a NumFOCUS Small Development Grant to implement granular access control for per-feedstock CI services. The target idea was to have mechanisms for the community to provide custom CI resources for a given feedstock, like GPU runners or larger instances for resource-intensive builds like PyTorch. We ended up providing a server a 6-GPU, 48-CPU server that conda-forge has used for 790K+ minutes now! Read more about in this blog post: Building a GPU CI service for conda-forge. Big thanks to Amit for his constant involvement in the setup and maintenance!

That work forced us to take a deeper look at our workflow templating in conda-smithy, and we realized that there were some performance improvements we could make. We contributed two additional runtime provisioning backends: micromamba and pixi. Using any of those instead of the default Miniforge installation brings the CI setup time under one minute in all platforms. This is a dramatic change specially for Windows, where it would often take 4-5 minutes before conda-build could even run.

One common review item in any submission to conda-forge is to analyse the contents of the produced artifacts. However, conda-build doesn't produce such output. We contributed a new list subcommand to conda-package-handling's cph utility that will report the files included in a conda artifact without extracting anything. We then added that subcommand as an additional logging step in the conda-forge build scripts. As a bonus, you can also use cph list with remote artifacts, using the same streaming techniques we leverage in conda-metadata-app!

Better UX interacting with the conda-forge bots

Getting involved with conda-forge's infrastructure for so long makes you discover small opportunities for better UX.

Some examples of the former include having the @conda-forge-admin commands react with the rocket emoji 🚀 as soon as an event is triggered so users have early feedback before the bot can perform the requested task. The @conda-forge-admin, please update version commands will also open as draft while the version is being fetched to avoid early notifications, and the title will be updated with the found version if successful for better commit messages upon merge!

Microarchitecture-aware package builds

conda-forge ships binary builds, so users don't have to compile anything on their machines. It should Just Work (tm) upon extraction. Compiled dependencies are built specifically for each platform and architecture (e.g., Linux running ARM or Windows running on x64). However, this also forces us to use compilation flags that target the most common chips, leaving some optimization opportunities for more modern CPUs on the table.

Isuru contributed archspec support for Windows, which finally allowed conda-forge to ship microarchitecture-optimized binaries across all platforms. While we recommend trying other methods first, like runtime dispatching to different variants of the same library, this method can be useful for libraries that cannot implement it. Use it sparingly, though; they can really explode your CI matrix!

Unblocking migrations

conda-forge heavily relied on automated migrations to upgrade and rebuild parts of its ecosystem. This is the main way in which we can guarantee that packages stay ABI compatible and up-to-date with newer library developments.

Axel contributed fixes and improvements to the new stdlib() Jinja function migration that allowed recipes to be more explicit about their base C library requirements. The MSYS2 stack was also rebuilt by Isuru, which unblocked a long-awaited R major version upgrade in Windows.

Community and governance

Contributing to an open source project always needs to take into account the constraints of the community that maintains it. We could not impose any changes without building consensus first, which involved interacting with many teams via different communication platforms. We took this opportunity to review some governance items, and help with day-to-day tasks that are not always particularly exciting.

Building consensus takes many forms and channels: community meetings, ecosystem specifications, Github issues, chat platforms. Since we had to rely on all of them in one way or another, we ended up contributing small improvements in many different places.

The conda-forge team meets every two Wednesdays to discuss a variety of topics. Notes are kept in HackMD documents that are then submitted as a PR to the conda-forge/conda-forge.github.io. This used to be a manual process, but we added a couple of Github Actions workflows to automate the creation of a new HackMD document from a given template, open a PR and then, once done with the meeting, sync back by adding a label (see example PR). Works pretty well for both conda-forge and conda community!

In addition to GitHub issues and PRs, the conda-forge community had a couple of rooms in Gitter (which then became Matrix / Element rooms). After spending some years on this platform, we found that it did not provide a good enough story for us. We proposed moving to Zulip via CFEP 23, which was approved by the core team. We have been using that platform successfully for a few months and submitted a similar proposal to the conda community (CEP 18), which was also approved. That means that both conda-forge and conda community are now using Zulip! Visit us at conda-forge.zulipchat.com and conda.zulipchat.com, respectively.

Conclusion

conda-forge's infrastructure is a very complex, never-stopping build service, made of numerous moving pieces put together and whose changes are very often deployed live to production. This makes the contribution process quite fragile and challenging, since no-one wants to be responsible for breaking something 20K+ repositories depend on. Documentation is scarce and the active maintainers who know the ins and outs of the setup can be counted with half a hand.

Over these two years we have learned a lot about it, though, and we have seen more and more contributors gathering up the courage to step in front of this seemingly untameable beast. We are incredibly grateful for Matthew R. Becker's (@beckermr) patience in attending all of our questions, proposals and suggestions. Without his active participation none of the infrastructure work could have gone through, and this is testament of the low bus factor numbers that threaten many open source projects, communities and ecosystem. We'd like to believe that after our work in the documentation efforts, and the many conversations we've had in issues and pull request set a precedent for many more folks to give it a try and help with sustaining the delicate garden that is conda-forge.

Our commitment with conda-forge does not end with this grant. We will stay involved in 2025 through our continuous participation in the community as contributors and core team members. There is still a lot to do! If you are interested to know more, find us in Zulip!

Acknowledgements

- The featured image is a photo by Jonny Gios on Unsplash.