Polars Plugins: let's make them easier to use

Published September 30, 2024

condekind

Bruno Kind

I am Bruno Kind, and this is the place where I tell the world about my journey in Open Source during July-September 2024. How I made it through an internship to work with Open Source, in an entry-level Rust position – yes, they're real! And how I managed to contribute and improve Marco Gorelli's existing Polars Plugin Tutorial. Hop in, grab your popcorn, fasten your seatbelts.

- What are Polars plugins?

- Prelude and first week

- Writing plugins and chapters

- Working at Quansight Labs

- New ideas to make plugins more approachable

- The end

- Acknowledgements

- Resources

What are Polars plugins?

Polars is a DataFrame library made in Rust and distributed in Python, R and NodeJS (besides Rust itself). How about plugins?

Expression plugins are the preferred way to create user defined functions. They allow you to compile a Rust function and register that as an expression into the Polars library. - Official docs

User defined functions are quite important in the context of DataFrames. Users of these other languages (Python, R, JS) might be tempted to write User Defined Functions (UDFs) in the language they're already using Polars with. However, plugins are a way to possibly increase the performance of these functions by orders of magnitude! By writing UDFs in Rust (as expression plugins), Polars is able to work more efficiently than if they were defined in the languages mentioned above. Expression plugins are a type of plugin, and the main target of this article - whenever you read plugin, I'm referring to expression plugins, unless stated otherwise. The other type is called an IO plugin, more on that later.

Prelude and first week

Sometime before the internship began, I was told my project would be related to Polars plugins. Thrilled, I rushed and wrote my first plugin, following the official tutorial, then... nothing. I'm not a Polars user, nor is my Rust-fu strong enough to explore the plugin system in-depth. But I did have an idea - what if I could make Conway's Game of Life play itself in a dataframe? Could plugins do that? Regardless, I had to wait. I lacked the juice.

Time passed, as it always does, and the internship began. I had my first days, met Marco (my mentor), talked to people from different areas, followed all the steps from the onboarding process, yada yada. It didn't take long for my end-goal to be presented to me, which was: to improve and make it easier to follow a Polars Plugin tutorial (the one authored by Marco).

I was having daily meetings with him, and he was encouraging me to follow the tutorial as well as explore plugins in general. And so I did. I went through the entire tutorial in the first days of the week, and eventually decided to share with him the crazy idea I had before it all started - making Conway's Game of Life "run" in a dataframe. What would you tell a lunatic intern with such a ridiculous idea? I don't know, but he said something along the lines of "I'm totally on board with it". This was it, the game was on! But wait, no... I don't know how to do that... I actually have no clue!

Those were my thoughts, initially. I believed the same limitations I had before the internship began were also present here, but that was not entirely true. After all, I did the tutorial, I played with some examples, and I even managed to "explain" to ChatGPT a broader context of plugins, allowing it to give me some useful suggestions besides its usual hallucinations. I could at least try something. Fast forward... a day? Two? It was done - for real. I couldn't believe myself.

You see, Conway's Game of Life is a cellular automaton which beautifully displays emergent behavior. Complex constructs from a very simple rule-set.

What needed to be done? I had to get the rule-set right, and manage to advance the simulation (iterate the rules). Assuming the dataframe would contain 0's and 1's only, I went ahead and broke the challenge into two smaller groups:

- I had to implement a plugin in Rust to sum the values of both neighbouring rows and columns. Then I had to decide what the element in the center would be in the next iteration: dead or alive, 0 or 1.

- I needed to find a way to step the simulation. For that, I wrote a Python script to repeatedly call the plugin, preserving the names of the columns (this way, columns from a new iteration would replace columns from the older one - this is a Polars specific detail).

After finishing those, the magic took place, the simulation was happening before my eyes:

During that week, I also learned about Narwhals, an amazing project started by Marco to provide DataFrame agnosticism when writing libraries. I managed to sneak in a minor contribution as well, just some test refactoring, but still - that made me happy!

Now what? I didn't improve the tutorial, I didn't make anything easier for end-users... yet. That was, after all, part of the exploration. An exercise, among others I had done.

During that first week, my only real contribution to the tutorial was creating a CI script to help manage pinned versions. That was fine, things were just beginning.

Writing plugins and chapters

As time went by, I explored and created more plugins, like a URL parser (making use of the url crate).

I learned about optimizations that could be applied to my code, profiled memory and runtime of the things I wrote.

The wind was good, and things were sailing well, but I was anxious to make progress in the tutorial.

Eventually the opportunity presented itself: writing a section about allocations for the Strings chapter.

While tasked with this, I also had the chance to work on a function that would end up in the Polars code itself: binary_elementwise_into_string_amortized.

I never imagined doing these things while having such a basic level of Rust (I'm still afraid of lifetimes!), but somehow it was possible... what a third week!

The days were passing and fortunately I was seeing constant progress of my end-goal: improving the tutorial.

I wrote a new chapter about a possible pitfall, in which users could be tempted to allocate and return a Vec<Option<T>> instead of just Vec<T>,

then started writing about... guess what? The Game of Life I made in the first week! Yes, that would find its way into the tutorial as well, who would've thought!?

This was a very step-by-step, holding-hands kind of chapter, with all the Rust and Python needed to make the plugin happen.

I was concerned about improving the tutorial and forgetting the "make it easier to use", so I was extra careful to write that chapter in a very beginner friendly way.

Then I got sick. Happens to all of us, but what a frustrating thing, not being able to advance, having little to report. It was annoying and took longer than I expected, but fortunately it wasn't anything serious, and I was able to pick up from where I left after a week of rest, give or take.

The allocations section I wrote was finally merged - we were waiting for some functions to be merged to Polars before publishing it, otherwise we'd need to update it shortly after writing the section. I started reading, then writing about arrays (which ended up being merged as a whole chapter), drafting ideas for the very text you're reading, and studying a bit of Narwhals and Dask, to be able to contribute more than just test-related PRs.

Working at Quansight Labs

Now's a good time to make a brief pause to talk about working at Quansight. Many readers might be familiar with remote work, and the things some companies do to avoid the burden of being isolated from your colleagues. Quansight not only has channels in Slack for us to share Qool personal projects and things (whence I learned there are lots of 3D-printer enthusiasts here), but the company also has events scheduled in which folk present their (mostly) nerdy projects and recent developments. There's also Donut - a bot that pairs people in its channel every week, so we get to talk to random people and know more about our colleagues. To be honest, as an introvert without the social superpowers regular people have, that scared me (still scares) a lot. But I told myself I'd be saying "yes" to as many things that were presented to me as possible, during this internship.

It did, and still does feel a bit forced, everytime that little bot messages me - can't simply wash away introversion like that, after all. But I never said no. Some donut-arranged calls were rescheduled, some never took place, but they never did-not-happen because of me. And I'm so glad this bot exists, I am so glad I told myself I'd be a "yes person" to this extra, completely optional activity.

I was meeting new people every week, and I quickly realized I'd have to find a way to completely shut down my impostor syndrome. I'm an intern, it's fine, I'm an intern, it's fine, I told myself. Why? Through Donut I met people who used to work at CERN. Well accomplished physicists with PhDs who grew bored of their old jobs. Mathematicians, folk from way outside the Computer Science circle I was used to, right there, talking to me, 1:1, as if we were equal. How amazing was that, I wanted so badly to be their full-time colleagues, but... sad-trombone sounds: unfortunately we, interns, knew from the start we wouldn't get hired.

Yes, that's right, in that sense, the internship program functions more like a Google Summer-of-Code type of program - Google doesn't offer you a job after it ends. But unlike GSoC, we're in the company while the program lasts. That was probably the one and only sad part of my whole experience working there. But even considering they wouldn't hire us, they were kind enough to have a "CV clinic" - a presentation that helped us prepare our CVs and resumes for us to apply to positions at other companies. They didn't have to do that, so I'd call it a nice move.

New ideas to make plugins more approachable

Back to work! Up until now, I haven't talked about a key term that kept haunting me: accessibility. I'm not sure I read that word explicitly somewhere, or if I made it up when thinking of "making a tutorial easier to use", but I couldn't stop thinking about accessibility. And to be fair, it's quite hard for me to work on it, as I've never dealt with it before (in-depth). Was it part of my job to make the tutorial more accessible? If so, I had a lot to do. Did I? Did it lack accessibility? I was confused and helpless.

Then, lightning struck. I realized I could only help with things I knew how to do, so there was no need to bash my head against a wall over features I couldn't implement. I had to draw a line. Pun intended - see, this is how I'd help the accessibility side of "improving the tutorial": by drawing! We had text and code blocks, maybe a benchmarking chart or two. I could draw diagrams and memory layouts that would've made a huge difference when I was first learning. It couldn't hurt to try.

The first thing I drew was a diagram showing the array memory layout. It was flat-out wrong. To be honest, I don't think it's worth dissecting this mistake - suffice to say, it wasn't something trivial. I ended up choosing to not include any picture for arrays, as I concluded the "intuitive" memory layout was the correct one - for some reason I thought it was different. What a great first diagram - nothing!

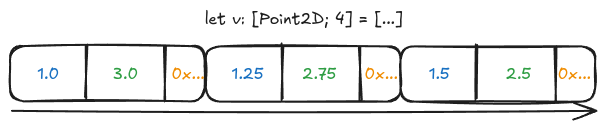

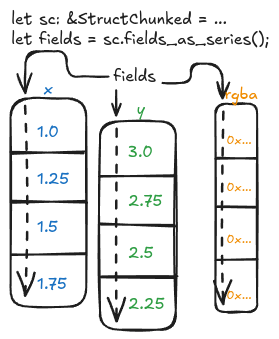

Mistakes happen, so I moved on. Next I was drawing diagrams showing how Polars stored structs under the hood, which is not intuitive. Assume we have the following struct defined in Rust:

struct Point2D { x: f64, y: f64, rgb: u32,}

Compare the following two diagrams, noting the difference between an array of struct instances in pure Rust vs. how Polars organizes a chunk of the same struct in memory:

This is due to Polars following Apache Arrow's columnar format. No need to get into more details, the point is: pictures help. A lot. So I continued drawing, making the tutorial more accessible. This went until the very end, which was sadly approaching.

The end

It was time to say goodbye, so I started wrapping things up, which unfortunately meant not finishing my work on IO plugins. Yes, there is another kind of plugins! But this is a very recent (as of this writing) and undocumented area. It should be enough to say I did manage to explore and write some IO plugins, but there wasn't enough time to write about them in an entire new section of Marco's tutorial (or another tutorial altogether). On the bright side, there's a lot of work for new interns in the next batches of the Open Source internship program!

Before the end of the internship, we even got some praise online!

And a user wrote on Linkedin:

[...] I have published three polars plugins to pyipi now. None would be possible without the excellent tutorial by Marco Gorelli of Quansight labs.

I'm glad we were able to help them, and hopefully many others to come. This is the end of my Summer journey in open source. I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Kind regards,

B. Kind

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Marco for all the support, patience, and time he dedicated to me during this internship.

I’m also grateful to Melissa for being the best internship coordinator one could ask for, with her guidance, sense of humor, and ever-present smile.

My fellow interns deserve thanks as well, for sharing their experiences weekly, offering help and insights, and always rooting for one another.

Finally, I’d like to thank Ralf, who interviewed me for what I believed to be the worst interview of my life (on my part). Somehow, he saw something in me and decided to give me a chance. I truly appreciate it and can only hope I made Quansight a tiny bit better.

Resources

- Tutorial: https://marcogorelli.github.io/polars-plugins-tutorial/

- Polars: https://github.com/pola-rs/polars/

- Narwhals: https://github.com/narwhals-dev/narwhals

- Both images (header and link in the https://labs.quansight.org/blog page) were generated by DALL·E