Writing fast string ufuncs for NumPy 2.0

Published May 21, 2024

lysnikolaou

Lysandros Nikolaou

NumPy 2.0

After a huge amount of work from many people, NumPy 2.0.0 will soon be released, the first NumPy major release since 2006! Among the many new features, several changes to both the Python API and the C API, and a great deal of documentation improvements, there was also a lot of work on improving the performance of string operations. In this blog post, we'll go through the timeline of the changes, trying to learn more about NumPy ufuncs in the process.

How it all started

Last July, the D.E. Shaw group, one of our customers, reported that string operations

were not performant. Their team had already looked into the issue and found an

obvious bottleneck. For every operation on string arrays, NumPy would create a

Python object and call the associated method in str or bytes (depending

on the array's dtype). It looked something like this in C pseudocode:

// Get the corresponding str methodmethod = PyObject_GetAttr((PyObject *)&PyUnicode_Type, method_name);<loop over the array> { // Create Python object out of the array item PyObject* item = PyArray_ToScalar(in_iter->dataptr, in_iter->ao); // call corresponding str method PyObject *item_result = PyObject_CallFunctionObjArgs(method, item, NULL); // add result to output array PyArray_SETITEM(resultarr, PyArray_ITER_DATA(out_iter), item_result);}

Consequently, performing a string operation involved the following costly operations:

- Creating a unicode or a bytes object from the array item.

- Calling the corresponding unicode or bytes method.

- Adding the resulting unicode or bytes object to the output array by converting back to the representation that NumPy understands.

And all that in a loop over all array items.

Creating the first ufunc - isalpha

The obvious solution to this was to operate on the raw C data in the NumPy array buffer and not rely on the Python round-trip. NumPy's ufunc mechanism is the right solution for doing just that. Here's a short excerpt from the NumPy documentation explaining ufuncs in a bit more depth:

A universal function (or ufunc for short) is a function that operates on ndarrays in an element-by-element fashion, supporting array broadcasting, type casting, and several other standard features. That is, a ufunc is a “vectorized” wrapper for a function that takes a fixed number of specific inputs and produces a fixed number of specific outputs.

When authoring a ufunc, a ufunc author must write a 1-dimensional loop, with the loop function having the following signature:

void loopfunc(char **args, npy_intp const *dimensions, npy_intp const *steps, void *data)

When invoking the ufunc, NumPy provides the following arguments:

- args: an array of pointers to the data buffer for the input and output arrays.

- dimensions: a pointer to the size of the dimension over which this function is looping.

- steps: a pointer to the number of bytes to jump to get to the next element in this dimension for each of the input and output arguments.

- data: arbitrary data (extra arguments, function names, etc. ) that can be stored with the ufunc and will be passed in when it is called.

When I first started looking into addressing these performance concerns,

I chose isalpha as the first ufunc I'd try to implement. Since isalpha is a function

with just one input and one output, the loop was relatively easy to write. It looked

something like this1:

voidstring_isalpha_loop(char **args, npy_intp const *dimensions, npy_intp const *steps, void *data){ // Get a pointer to the input and output data buffers char *in = args[0]; char *out = args[1]; // Get number of items to loop over npy_intp N = dimensions[0]; while (N--) { npy_bool res = string_isalpha(in); // Write the result to the output buffer *(npy_bool *)out = res; // Jump to the next element in the array in += steps[0]; out += steps[1]; }}

Within the loop function, we do the following:

- Get a pointer to the input and the output data buffers using the

argsargument. - Loop over all of the items in the arrays by using the

dimensionsargument, and, for each item, do the following:- Use the input buffer to call

string_isalphaand get a result back. Note that we do not include the implementation ofstring_isalphahere, because the implementation itself is irrelevant to the ufunc mechanism. - Write the result to the output buffer.

- Jump to the next element in the array by adjusting the input and output

pointers using the

stepsargument.

- Use the input buffer to call

The results from writing a ufunc for isalpha showed that writing ufuncs really

was the way to go (more on this later), so from this point on, the real work of

writing ufuncs for all the string operations began.

A brief digression: Fixed-length string dtypes

In order to understand the rest of the article, it's important to have an idea of how strings are represented in memory in NumPy. NumPy, as of NumPy 1.26, has two string dtypes, one for Unicode (UTF-32) and one for bytes (ASCII). Both of these dtypes are fixed-length dtypes, which means that the maximum length of each array item is specified by the dtype. Let's take the following example:

>>> import numpy as np>>> s = np.array(["abcd"])>>> sarray(['abcd'], dtype='<U4')

The dtype='<U4' tells us that the strings in this array have a maximum length

of four characters. Were we to assign an item of the array to a string that's

longer than that, the excess characters would be stripped:

>>> s[0] = 'efghi'>>> sarray(['efgh'], dtype='<U4')

That doesn't mean, however, that all of the array items have to be exactly four characters long. We can have array items that are smaller than that. The underlying array buffer still allocates the number of bytes corresponding to four characters (4 bytes for ASCII, 16 bytes for UTF-32), but the rest of the bytes are zero. That has the side-effect that both of these dtypes strip all trailing zero bytes.

>>> s = np.array([b"abc", b"defgh"])>>> sarray([b'abc', b'defgh'], dtype='|S5')>>> s.tobytes() # View raw datab'abc\x00\x00defgh'>>> s[0] = 'a\0\0'>>> sarray([b'a', b'defgh'], dtype='|S5')>>> s.tobytes()b'a\x00\x00\x00\x00defgh'

Now back to our string ufuncs.

Next up was add

Next on our list of functions to implement was add. This was not a new ufunc

as np.add already existed for other dtypes. All we had to do was just implement

the new loop (which was essentially the same as isalpha with just one more input)

and everything would be fine, right? Wrong! As soon as I built NumPy and ran a

Python REPL to test, I was met with the following error:

>>> import numpy as npTraceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> File "/numpy/build-install/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/numpy/__init__.py", line 114, in <module> from numpy.__config__ import show as show_config File "/numpy/build-install/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/numpy/__config__.py", line 4, in <module> from numpy._core._multiarray_umath import ( File "/numpy/build-install/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/numpy/_core/__init__.py", line 23, in <module> from . import multiarray File "/numpy/build-install/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/numpy/_core/multiarray.py", line 10, in <module> from . import overrides File "/numpy/build-install/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/numpy/_core/overrides.py", line 8, in <module> from numpy._core._multiarray_umath import (TypeError: must provide a `resolve_descriptors` function if any output DType is parametric. (method: templated_string_add)

The important part of this traceback is the error message: must provide a

resolve_descriptors function if any output DType is parametric. That is a very

fancy way to say that NumPy does not know enough about the output dtype in order

to be able to register the loop. Remember that isalpha returns booleans. That's

easy enough for NumPy to do, since booleans are fixed-size dtypes. However, string

dtypes, both unicode and bytes, are parametric dtypes, meaning that their size

is dependent on the array items, specifically their lengths. In order for NumPy

to be able to register the loop, it needs a resolve_descriptors function which

specifies the parameters for all the necessary dtypes. This function has the

following signature:

NPY_CASTING resolve_descriptors(struct PyArrayMethodObject_tag *method, PyArray_DTypeMeta **dtypes, PyArray_Descr **given_descrs, PyArray_Descr **loop_descrs, npy_intp *view_offset)

The important arguments here are given_descrs and loop_descrs:

given_descrsis an array of input and output (if any were given by the user, more on this in the next paragraph) descriptor instances. A descriptor instance is a descriptor for an array, and includes information about the size of each item.loop_descrsis an array of descriptors that must be filled in by the resolve descriptors implementation. These will be the descriptors that will be used in order to call the loop with the correct information. More information can be found in the NumPy documentation forNPY_METH_resolve_descriptors.

If you're wondering how the user can pass output dtypes to the resolve_descriptors

function, that's the work of the out optional keyword argument (kwarg) to ufuncs. If the

out kwarg is None, which is the default, a new array will be created for each of the

outputs. If one passes an array through the out kwarg however, the results will be

written into the out array, and that array will be returned. In that case, the out

array descriptor will be the last item in given_descrs. Let's see that in practice:

>>> a = np.array([1, 2, 3])>>> b = np.array([6, 7, 8])>>> aarray([1, 2, 3])>>> barray([6, 7, 8])>>> np.add(a, b)array([ 7, 9, 11])>>> aarray([1, 2, 3])>>> barray([6, 7, 8])>>> np.add(a, b, out=a)array([ 7, 9, 11])>>> aarray([ 7, 9, 11])>>> barray([6, 7, 8])

For add, writing a resolve_descriptors function is relatively straightforward,

since the size of the result dtype should be the sum of the two input-dtype sizes,

so that we get something like this:

>>> a = np.array(['abc'])>>> b = np.array(['def'])>>> aarray(['abc'], dtype='<U3')>>> barray(['def'], dtype='<U3')>>> np.add(a, b)array(['abcdef'], dtype='<U6')

Notice how the result array has a dtype of <U6. Thus, the resolve_descriptors

function will look something like this:

NPY_CASTINGstring_addition_resolve_descriptors(PyArrayMethodObject *self, PyArray_DTypeMeta *dtypes[3], PyArray_Descr *given_descrs[3], PyArray_Descr *loop_descrs[3], npy_intp *view_offset){ // Don't mess with the input descriptors. loop_descrs[0] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[0]); if (loop_descrs[0] == NULL) { return _NPY_ERROR_OCCURRED_IN_CAST; } loop_descrs[1] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[1]); if (loop_descrs[1] == NULL) { return _NPY_ERROR_OCCURRED_IN_CAST; } // Create a new descriptor instance from the first input and add // the element size of the second input. loop_descrs[2] = PyArray_DescrNew(loop_descrs[0]); if (loop_descrs[2] == NULL) { return _NPY_ERROR_OCCURRED_IN_CAST; } loop_descrs[2]->elsize += loop_descrs[1]->elsize; return NPY_NO_CASTING;}

It does the following:

- Specifies that the input dtypes are the ones that should be used for passing information to the loop. In doing so, it also ensures that the dtypes are in canonical representation, meaning in the underlying system's native byte order.

- For the output dtype (

loop_descrs[2]), we create a new descriptor instance from one of the inputs (either one would be fine), and then add the other's element size. This way, we get an output dtype with a size that's equal to the sum of the sizes of the two input dtypes.

After registering the resolve_descriptors function, everything works correctly

and np.add now works for string dtypes as well!

find / rfind: Nothing new here, right?

Next in our list of functions to implement as ufuncs were find and rfind. Like

isalpha, these two return fixed-type dtypes (ints), so no need for a

resolve_descriptors function, and they both would be new ufuncs. Unlike

isalpha though, which only has one input argument, they both accept four input

arguments: the buffer to search in, the substring to search for, and starting and

ending indices (if one wants to specify in what part of the buffer to search). The

starting and ending indices can be of any integer dtype (int8, int16, int32 etc.),

but we only want to write one loop for all of them. To achieve that we need a promoter.

A promoter is a function that specifies the promotion rules for a ufunc. In general, a ufunc will search for a loop that matches the input dtypes exactly. In order to be able to accept more than one input dtype, and have all of those dispatch to the same loop, we should register a promoter. A promoter has the following signature:

int promoter(PyUFuncObject *ufunc, PyArray_DTypeMeta **op_dtypes, PyArray_DTypeMeta **signature, PyArray_DTypeMeta **new_op_dtypes)

The two important arguments here are op_dtypes and new_op_dtypes. Similar

to the resolve_descriptors function, op_dtypes are the dtypes the user passed

into the ufunc. new_op_dtypes is an array of dtypes that must be filled with

the dtypes the input should be promoted to before searching for a loop.

For our specific example, we only want to write one loop for int64 (i.e. an 8-byte integer). Thus, all integer inputs should be promoted to int64 before searching for a loop. Our promoter will then look like this:

intstring_find_rfind_promoter(PyUFuncObject *ufunc, PyArray_DTypeMeta *op_dtypes[], PyArray_DTypeMeta *signature[], PyArray_DTypeMeta *new_op_dtypes[]){ // Do not promote the first two arguments (haystack and needle) Py_INCREF(op_dtypes[0]); new_op_dtypes[0] = op_dtypes[0]; Py_INCREF(op_dtypes[1]); new_op_dtypes[1] = op_dtypes[1]; // Promote any other type to int64 for the next two arguments (indices) new_op_dtypes[2] = PyArray_DTypeFromTypeNum(NPY_INT64); new_op_dtypes[3] = PyArray_DTypeFromTypeNum(NPY_INT64); // Use default integer as the output type new_op_dtypes[4] = PyArray_DTypeFromTypeNum(NPY_DEFAULT_INT); return 0;}

Our promoter specifies the following:

- For the two string arguments, we do not allow promotion. We take the input dtype as is.

- For the two integer inputs, we allow other dtypes and promote all of them to int64.

- The output dtype will be the default integer dtype.

Doing all of this allows us to do the following, having only written one loop:

>>> buf = np.array(["abcd", "cdef"])>>> sub = "c">>> start = np.array([3, 0], dtype=np.int8)>>> end = np.array([4, 4], dtype=np.int8)>>> np.strings.find(buf, sub, start, end)array([-1, 0])>>> start = np.array([3, 0], dtype=np.int16)>>> end = np.array([4, 4], dtype=np.int16)>>> np.strings.find(buf, sub, start, end)array([-1, 0])

Last stop: replace

The last ufunc we're going to talk about is replace. First, let's remember that

replace accepts four arguments: the buffer to search in, the substring to search for

and replace, the replacement string, and a final integer argument that specifies

the maximum number of replacements to do. Putting everything we've covered so far

together gives us the following tasks:

- Write a loop for the string dtypes and int64.

- Add a promoter that promotes other integer dtypes to int64 for the last argument.

- Write a

resolve_descriptorsfunction that specifies the output dtype size.

But, wait! Those that paid attention to the section about add will remember that

the resolve_descriptors function does not get access to the data itself; it only

gets access to the array descriptors that contain meta information about the array.

By just looking at the input dtype sizes though, we do not know how many replacements

we'll have to do, and how long the final string will be. In order to circumvent

that, we have to create a Python wrapper around the ufunc written in C++ and use

the out kwarg, which I described above, to pass an array with the

correct dtype into the replace ufunc. All we have to do is find out what the maximum

length is, which, through some NumPy magic, is easy enough:

buffersizes = str_len(arr) + counts * (str_len(new) - str_len(old))

It's just the difference in size between the substring to be replaced and the replacement string, multiplied by the number of replacements. This leads to to the Python wrapper looking something like this:

def replace(a, old, new, count=-1): # Convert all input arguments to arrays arr = np.asanyarray(a) a_dt = arr.dtype old = np.asanyarray(old, dtype=getattr(old, 'dtype', a_dt)) new = np.asanyarray(new, dtype=getattr(new, 'dtype', a_dt)) # Count the number of occurrences of `old` in `a` # and compare that to the number of maximum replacements max_int64 = np.iinfo(np.int64).max counts = _count_ufunc(arr, old, 0, max_int64) count = np.asanyarray(count) counts = np.where(count < 0, counts, np.minimum(counts, count)) # Compute buffer sizes, construct output array and call ufunc buffersizes = str_len(arr) + counts * (str_len(new) - str_len(old)) out_dtype = f"{arr.dtype.char}{buffersizes.max()}" out = np.empty_like(arr, shape=buffersizes.shape, dtype=out_dtype) return _replace(arr, old, new, counts, out=out)

The only thing remaining now is to require that out should not be None

when calling the _replace internal ufunc. We can do that easily in the

resolve_descriptors function:

NPY_CASTINGstring_replace_resolve_descriptors(PyArrayMethodObject *self, PyArray_DTypeMeta *dtypes[5], PyArray_Descr *given_descrs[5], PyArray_Descr *loop_descrs[5], npy_intp *view_offset){ // Error in case the last item of given_descrs (the output descriptor) // is NULL which means that out=None. if (given_descrs[4] == NULL) { PyErr_SetString(PyExc_ValueError, "out kwarg should be given"); return _NPY_ERROR_OCCURRED_IN_CAST; } loop_descrs[0] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[0]); if (loop_descrs[0] == NULL) { return _NPY_ERROR_OCCURRED_IN_CAST; } // Omit the checks for NULL for conciseness (they're there in reality) loop_descrs[1] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[1]); loop_descrs[2] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[2]); loop_descrs[3] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[3]); loop_descrs[4] = NPY_DT_CALL_ensure_canonical(given_descrs[4]); return NPY_NO_CASTING;}

With this function in place, the _replace internal ufunc will fail as expected when

out is not provided. To get a better interface and avoid the need for an out array

one can use the numpy.strings.replace wrapper.

>>> a = np.array(["abc"])>>> out = np.empty_like(a, shape=a.shape, dtype="U3")>>> _replace(a, "b", "c", 1)Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>ValueError: out kwarg should be given>>> _replace(a, "b", "c", 1, out=out)array(['acc'], dtype='<U3')>>> np.strings.replace(a, "b", "c")array(['acc'], dtype='<U3')

Results

The benchmarks we ran were not too extensive, but the few results we had were already so promising, that we decided that doing all of this for all of the string operations was definitely going to be worth it.

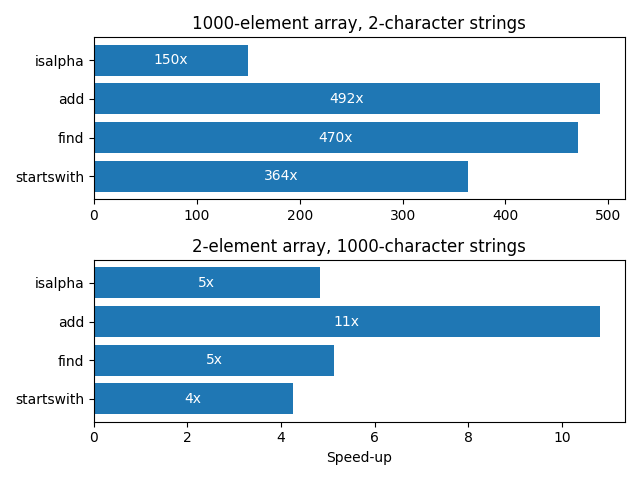

More specifically, we ran two experiments. One with a very small array with relatively long strings and one with somewhat larger array that only contained short strings. Here's an illustration of the exact results:

The results clearly illustrate a big performance improvement, especially for larger arrays. In the benchmarks we ran with a 1000-element array, there was a performance increase of 150x-492x depending on the string operation, while there was a more moderate speed-up of 4x-11x for smaller two-element arrays. This goes to show that operating on the raw C data, instead of doing the CPython PyObject dance explained above, has a very significant effect.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we explained how an observation from our client, the D.E. Shaw group,

led to a complete rework of how string operations are done for NumPy arrays.

In the process, we went over how to write ufuncs that operate on the raw C

data buffer of the array and we described how the resolve_descriptors function

can be used to let NumPy know what the output dtype will be for parametric

dtypes. We also briefly touched upon how to write a promoter function so that

we can write only one loop that can operate on multiple dtypes.

But that's not all! While all of this was brewing, Nathan Goldbaum

was also working on a variable length string dtype with support for UTF-8.

Combining these two work streams, NumPy 2.0 comes with a new numpy.strings

namespace that implements fast ufuncs for most of the string operations (with more

to come soon!) with support for byte strings (ASCII) and unicode (both UTF-8 and

UTF-32).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nathan Goldbaum, Sebastian Berg, Marten van Kerkwijk and Matti Picus for their countless reviews and all of their patience.

A big thank you to the D.E. Shaw group for sponsoring this work.

Footnotes

-

In reality, the string ufuncs look similar to this, but have some differences. Because they're internal to NumPy and because they need to have access to some additional data, they use a different signature. Also, since they have to support both

str(which, in NumPy, means UTF-32) andbytes(AKA ASCII) they are templated in C++. ↩