From napari to the world: how we generalized the `conda/constructor` stack for distributing Python applications

Published February 3, 2025

jaimergp

Jaime Rodríguez-Guerra

What do a visualization library and a package manager have in common?

Despite what one thinks, napari and conda have more things in common than meet the eye. The answer lies in application distribution stories and open-source collaboration. Keep reading to discover how the migration of napari installers from Briefcase to conda/constructor led to a beautiful open source synergy full of upstream contributions and collaborations.

About napari and its constraints

napari is a free, open-source library for n-dimensional image visualization, annotation, and analysis. It is written in Python so that you can use it directly in your notebooks and workflows, but it also ships a Qt application that can be used as a standalone UI. It is primarily used by researchers working on some scientific imaging disciplines, like microscopy, tomography, medical imaging, etc., but nothing stops you from using it for other types of images! You can learn more about what it can do for you in their PyCon AU 2024 talk.

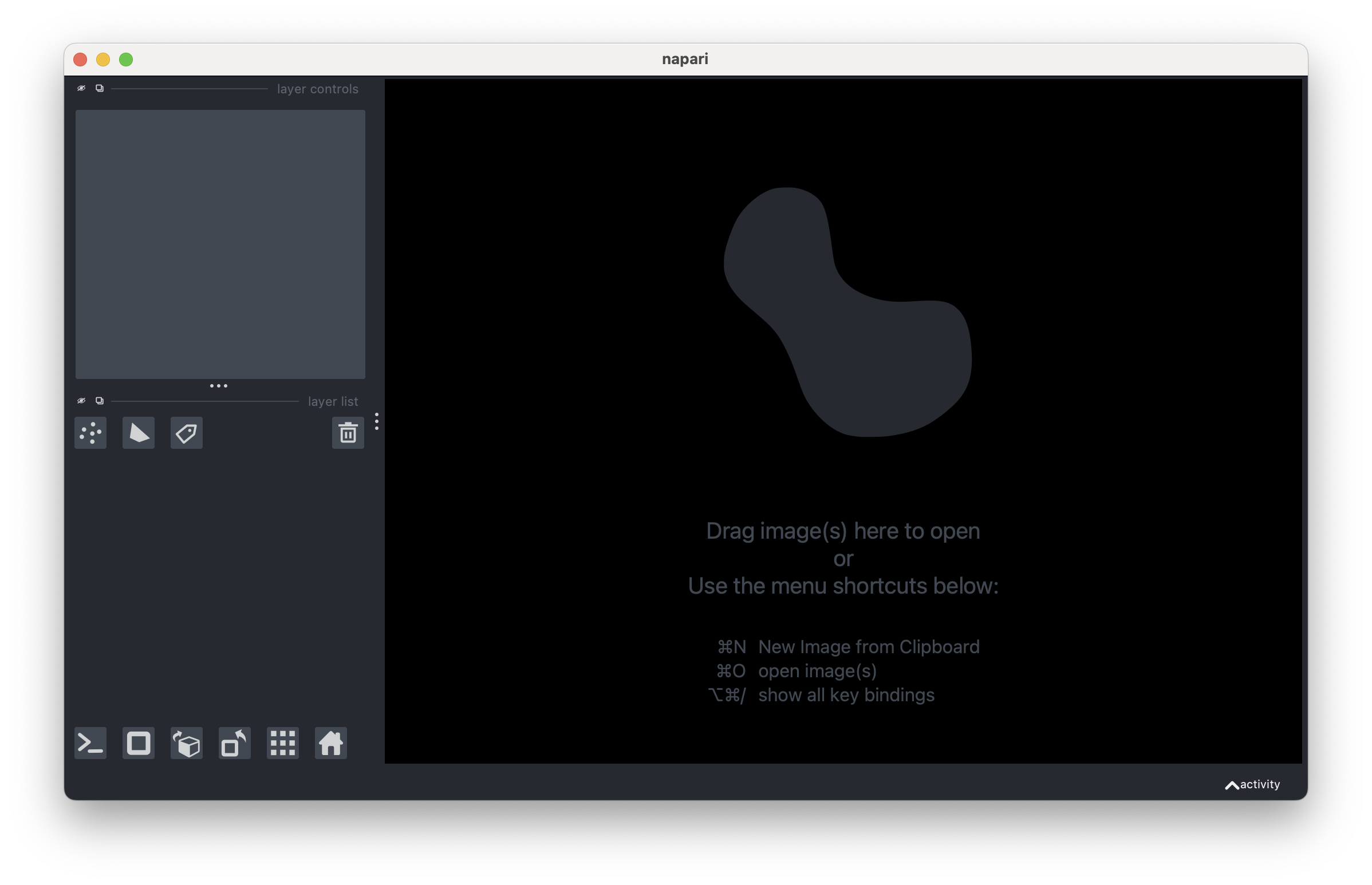

As a Python project, it is distributed via PyPI and conda-forge, so the usual installation process involves creating some sort of virtual environment and using your favorite package manager to fetch and extract the project and its dependencies in the desired location. To launch the Qt application, you type napari and you are greeted with this UI:

We were tasked with creating an installation story targeting the users of the Qt application, so we had to take into account the following requirements:

- It should not require end-users to interact with the command line at all.

- The look and feel should be as native in each operating system as possible.

- The whole process should only consist of a click-through journey until napari shows up in the desktop.

- It must be easy to update.

- It must be extendable with plugins.

- It should be as robust as possible, meaning it should not break with common tasks like installing a plugin.

Surely, we are not alone in this field, right? There must be a lot of tools available to build installers out of Python applications. It's Python, after all; it's immensely popular! Right? You've possibly heard of PyInstaller, Nuitka, Briefcase and many others, right? The Dropbox desktop client is also written in Python and Qt, and it works perfectly; why wouldn't we be able to do something similar?

A new installer generation pipeline

When we started working on napari, it was already publishing graphical installers, using BeeWare's Briefcase. Briefcase allows you to take your Python code and its dependencies, and bundle them in a OS-native installer, including iOS and Android! The dependencies are fetched from PyPI, except for the Python interpreter, which is obtained from their "Python support" packages.

After assessing the state of the art, we concluded that Python packaging alone had some foundational issues that would prevent us from meeting our packaging needs when it came to fostering a robust plugin ecosystem. We came up with one of the first Napari Advancement Proposals (NAPs), NAP-2, where we discussed the rationale and expected outcomes of our work.

In NAP-2 we proposed dropping PyPI packages as the source for our installers, in favor of conda packages built on conda-forge. Moving to conda-forge based distribution had a series of instant advantages:

- Community-governed repository of ABI cohesive libraries and interpreters.

- Qt support for Apple Silicon (which was not available in PyPI back then).

- More accurate packaging metadata thanks to the initial review process and the repodata patching mechanisms.

In practice, moving to conda-forge also forced us to move away from Briefcase, because it didn't support conda packaging. While briefly contemplating contributing such a feature to Briefcase, we decided to bet on tooling explicitly built for the conda ecosystem. This is the "constructor stack", which includes:

constructorproper: this is the CLI tool that allows users to create Windows, Linux and macOS installers made of conda packages. On Windows, it uses NSIS to create a graphical installer. On Linux and macOS, a fat shell script is used. In macOS, native PKG installers can also be generated, but they were heavily marked with Anaconda branding.menuinst: this is the library that creates shortcuts for Windows. It consumes JSON documents placed under theMenu/directory of a conda package. We needed to extend this to all platforms, each in its own native way.conda-standalone: a PyInstaller-frozen copy ofcondaused internally by the installers generated withconstructor. It needed some cleanups and compatibility with the new features added inconstructorandmenuinst.condaitself, the package manager, because it needs to be compatible with the newmenuinstand then bundled inconda-standalone.

A fresh breeze of air in constructor

When we started this project, the constructor repository had not been really maintained for a while. However, it was actively used by very important Python distributions: Anaconda used it for Miniconda and Anaconda Distribution, and conda-forge built Miniforge with it. There was a caveat though: the lack of activity in the repository forced its users to fork it to address blocking issues or adding necessary features.

So we did the same. The "napari fork" experiment resulted in a very long list of bug fixes and new features:

- Add features to allow for custom branding options for macOS PKG installers (they were initially built with hardcoded Anaconda branding)

- Add signing for Windows to avoid SmartScreen warnings

- Add notarization for macOS PKG installers to avoid security-related alerts

- Add support to ship multiple environments with a single installer so we can have a

base-like environment with justcondaandmamba, and anapari-specific environment with our application for robustness. - Other small fixes and improvements

Once we were satisfied with what our fork could do, we decided to upstream all those changes back to conda/constructor. This would ensure that the community as a whole can benefit from the improvements and fixes, while sharing the burdens and privileges of the associated maintenance costs. Part of the initial work was upstreamed in constructor 3.4.0, and we kept adding more and more features as the different pieces could fit together (e.g. we could not add menuinst support until we had released menuinst 2.0, which required the approval of its corresponding CEP).

The momentum generated by this collaboration enabled more contributions from the community. Since the 3.4.0 milestone, we have merged 200+ PRs, published 17 more releases, and established a maintenance team! Among the new features added since then, you can find lockfile support (which is the basis for thin installers that require an internet connection instead of the fat offline artifacts we generate now), better provenance metadata, cross-platform uninstallation, customizable extra pages in EXE and PKG installers, and system compatibility checks before the installation starts.

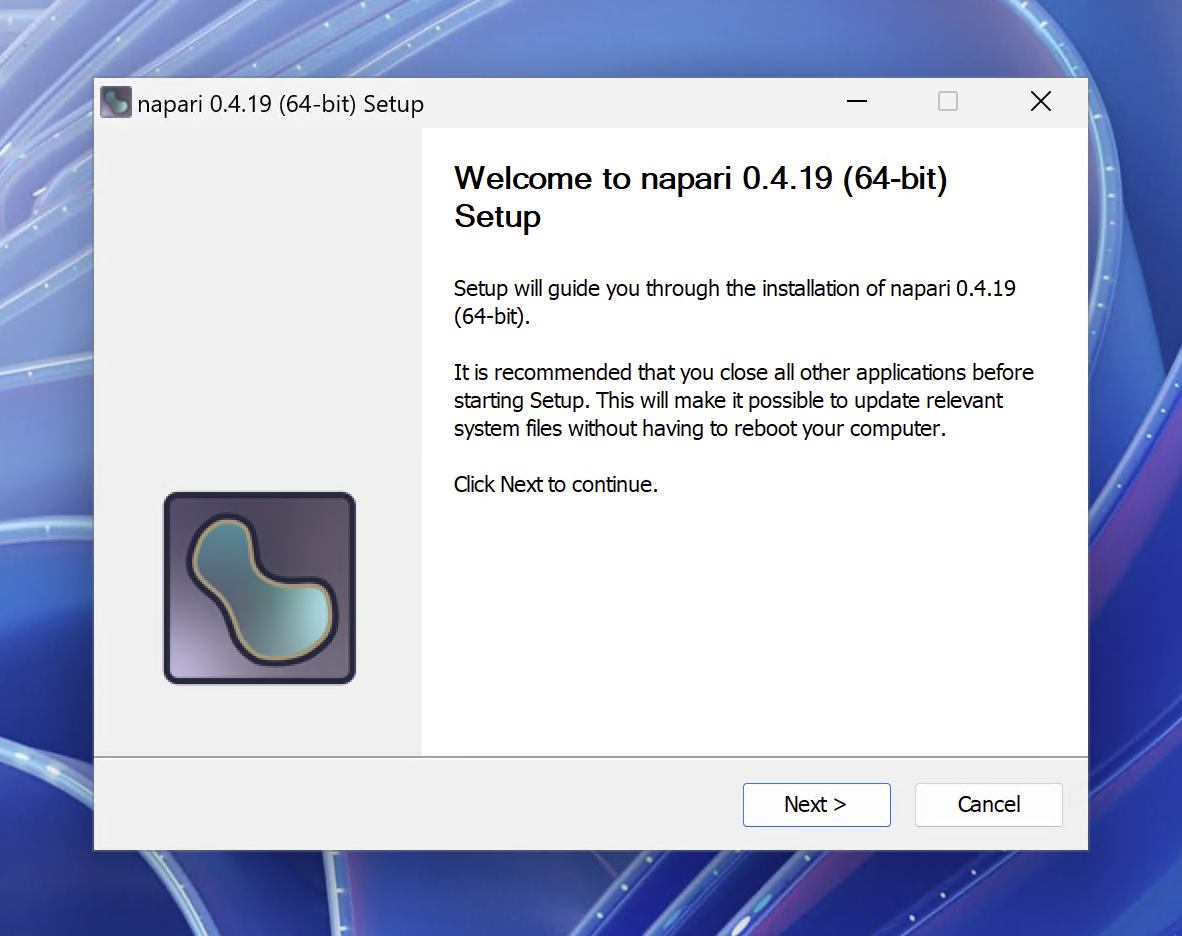

constructor generates installers that look like this on Windows. This is the welcome screen of the installer for napari 0.4.19.Multiplatform menu shortcuts with menuinst v2

With the changes in constructor, we could install napari in the three main operating systems, but we still needed to provide our users a nice way of launching napari from their desktop UI. Anaconda and conda-forge had relied on menuinst to provide Windows shortcuts for some years now, but Linux and macOS had no equivalent feature. After all, those users were already familiar with CLIs and the terminal.

But napari is not a CLI application. It's a GUI one. Its users are not expected to interact with a terminal just to launch it. They'd like to use an icon on their desktop that launches the main application directly.

menuinst did have support for Linux, but it used a slightly different input file than Windows and had not been tested or maintained ever. So we set to unify the schemas, extend it for macOS and rewrite it from scratch while maintaining backwards compatibility with the old Windows format. The result was CEP-12 and menuinst v2, which has the following features:

- A single input file provides native Windows, macOS, and Linux support

- The menu items can be fully customized: names, icons, target applications, starting working directories...

- The application can be associated with file types and URL protocols, which includes custom Swift launchers to listen to Apple events in macOS

- Full environment activation before the application starts

This was quite fun to implement, I must say. While Windows and Linux have a more-or-less defined set of standards or practices for these elements, we had to come up with a custom design for macOS: a shim .app directory that launches to the binaries in the conda environment while respecting system constraints like access policies, UI integration and Apple events.

conda and conda-standalone

Internally, constructor relies on single-binary executable of conda built with PyInstaller: conda-standalone. This special binary implements a secret subcommand, conda constructor, which helps with some install-time tasks like extracting and linking the conda packages in the target directory or running menuinst to create the cross-platform menu items.

This project did not have a home repository when we started, and its source was distributed separately in the feedstock repositories for both conda-forge and Anaconda. Over time, these sources had diverged. We tidied this up by creating a new repository at conda/conda-standalone which unified the two variants and provided an official place for its development.

Having a home for a project like this is essential. Thanks to this, conda-standalone has now seen more community contributions and improvements. One such contribution is the ability to uninstall conda installations via conda-standalone.

Extending napari via napari-plugin-manager

napari is meant to be extensible and has a healthy ecosystem of plugins written in Python. These plugins can add support for new image formats, analysis workflows, and other imaging tasks. They often fall into computer vision, machine learning, and automated annotation. This all translates to heavy dependencies and a lot of scientific code. In other words, packaging nightmares! This was one of the main reasons for relying primarily on conda-forge packaging.

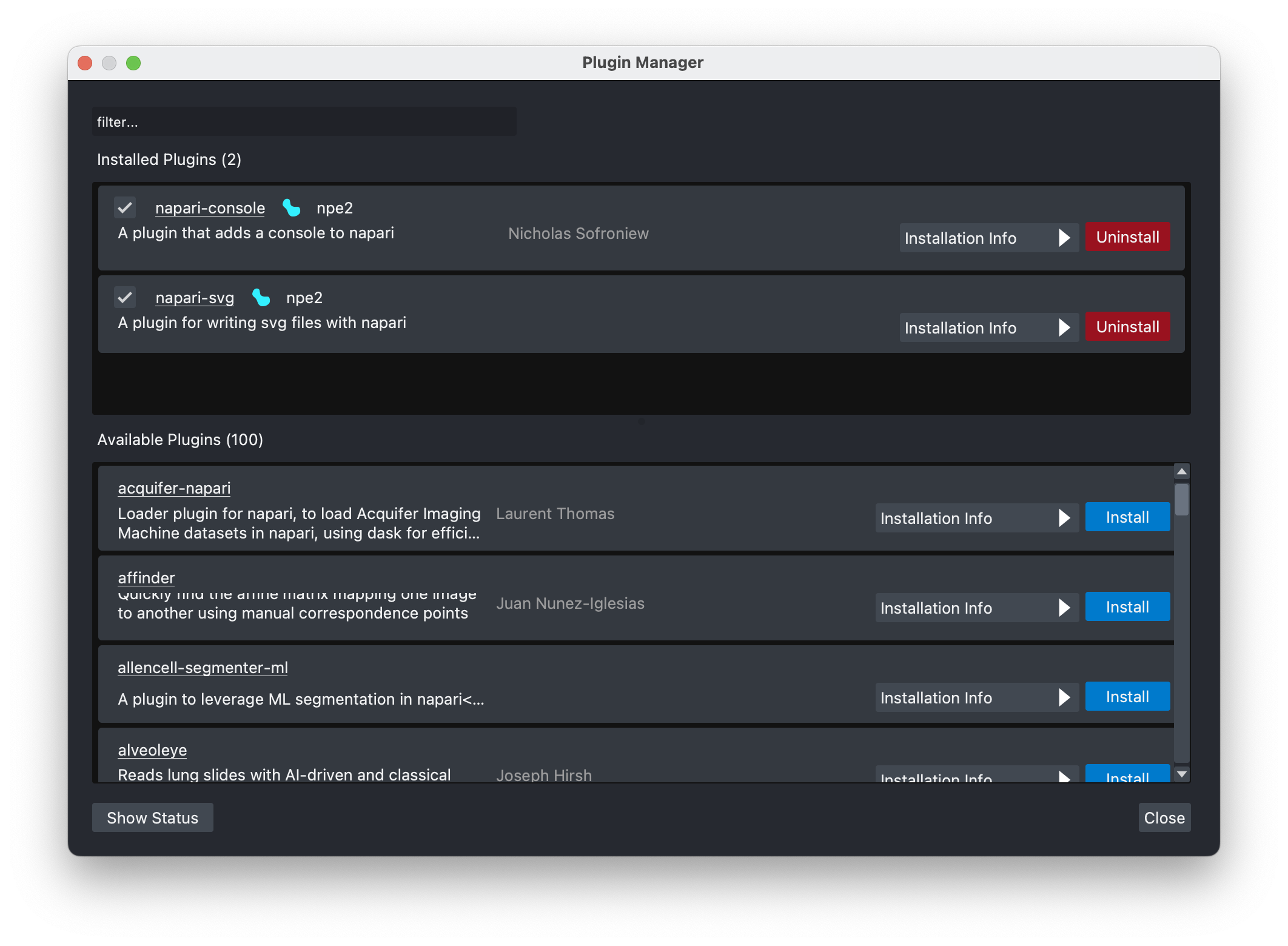

When we started contributing to napari, it already had a Plugin Manager dialog that allowed users to install selected packages from PyPI using pip. The discovery process was based on the presence of the Framework :: napari classifier. Packages that displayed that metadata were collected in the napari Hub website and the napari plugins API.

To be fully integrated with the constructor-generated installers, we added support for conda-based plugins. In the presence of such an installation, the plugin manager will offer to install plugins from conda-forge first, for better compatibility. The user can still choose to install from PyPI if they really want, shall they assume the associated risks of mixing conda and compiled wheels.

After some more work and UI refinements, we refactored the associated modules into its own package and repository. You can now find it in napari/napari-plugin-manager, featuring a napari-agnostic base class for easy reusability in other projects.

However, plugins are mainly developed by scientists whose main occupation is not software engineering. It's not surprising that packaging best practices is not in their list of main interests, and there's no one to blame for that. That meant that most plugins wouldn't ever make it to conda-forge because the authors were not interested or even aware of its existence.

While we helped package a good chunk of the plugin ecosystem in conda-forge (300+ so far), we had to also make sure pip-driven workflows would still work. We ran several experiments here (one of them became conda-pypi), but eventually settled for simply allowing PyPI installations after presenting a warning to the user. After all, we had dangerously ventured into the rabbit hole of trying to fix problems inherent to Python packaging, not napari-specific challenges. (Psst! Stay tuned if you want to know more about conda-pypi!)

Instead, we decided we should focus on recoverability first: we created a conda plugin named conda-checkpoints. Its purpose is simple: every time an environment is modified by conda in any way, write down a timestamped @EXPLICIT lockfile under $PREFIX/conda-meta. Other tools can use this file to regenerate the environment in the event of an error. Unfortunately, this lockfile format does not natively support PyPI dependencies. In the future, we hope this ends up triggering some kind of standardization effort to recognize an official lockfile format for the conda ecosystem, maybe inspired by conda-lock or Pixi.

Checking updates with napari-update-checker

Applications usually include user-friendly affordances to notify end users of the availability of new versions. Oftentimes, the notification includes a way to install the new version automatically. Sometimes, the application is even upgraded in the background and available after a restart.

We needed a similar feature for napari, but... how can we make that happen? conda environments that can be extended with arbitrarily-sourced plugins are not the easiest thing to upgrade. Instead, the idea would be to create new environments for each new version, and try to migrate as many plugins as possible without getting too much in the way.

The logic governing this process could not live in napari itself because we might run into bootstrapping issues (e.g., how do you fix a bug in the updating logic if to ship that you need to... update napari?). Thus, a new project was born: constructor-manager. This dual CLI/GUI application was designed in a napari-agnostic way so it can be used for any application distributed with constructor.

However, we did not fully finalize that vision, and instead we have an intermediate solution for now: napari-update-checker, a napari plugin that will notify the user of new versions. It compares the current version against a known remote source of truth for latest releases, while making sure all other possible napari versions in the installation are taken into account (e.g. it won't notify you if you are using napari 0.5 and 0.6 is available, but there's a napari 0.6 in a sibling environment).

Reflections on the ripple effects in open-source

The renewed activity in conda/constructor and the rewrite of menuinst attracted more community contributions and ended up having quite the ripple effect: Anaconda and conda-forge contributed their patches too, and both moved back to using the mainline version, with no forks. Other projects adopted it for their installers too, like Spyder IDE and MNE-Python. The folks at Prefix.dev are also implementing CEP-12 for rattler now, which will open a new world of possibilities in Pixi.

The Spyder team is also interested in reusing the plugin manager written for napari, so we have been refactoring some bits so other communities can reuse the common elements and adopt it in their applications. Dealing with the coexistence of conda and PyPI packages in the same environment led us to investigate better patterns at conda-pypi, which is now being incubated for wider usage in the conda ecosystem. And because we need to control which versions can coexist in a given napari version distribution, we ended up writing and deploying conda-subchannels as a way to vendor subsets of major channels, which was only possible due to CEP-15.

The recovery scenarios planned by constructor-manager required the application of a post-command plugin to create checkpoints after each change in the environment, which led to the conda-checkpoints experiment.

So yes, quite the ripple effect! For completeness, this is a list of all the projects impacted by our packaging work in napari!

Maintenance and upstreaming efforts:

constructormenuinstcondaconda-standalone

New projects:

napari-plugin-managernapari-update-checkerconstructor-managerconda-pypiconda-checkpointsconda-subchannel

Note that many of these conda plugins will probably end up generating the need for new plugin hooks in conda, further triggering new contribution echoes in the community. See issues conda#14070 and conda#13795 for some examples.

Fun fact: the napari community uses Zulip heavily as their communication channel. This might have had a deeper-than-you-think impact in how the conda-forge and conda communities chat and interact. After countless messages on Gitter.im / Matrix.org, they also moved to Zulip in late 2024! As a long contributor to those communities, I'm very excited about this new conversation format. Tracking topics and to-do items is a breeze now, compared to the "that-thread-reply-from-yesterday?ha-good-luck-finding-it" workflow in Matrix.org. It looks like a few communities (see Jupyter) and companies (e.g. QuantStack) in the PyData space are also moving there! Ripple effects, indeed.

If you also want to package your Python application and need an easy-to-run installer that works for all platforms, give conda/constructor a try!

Acknowledgements

- The Quansight Labs team: Gonzalo Peña-Castellanos, Daniel Althviz, Isabela Presedo-Floyd, Melissa Weber Mendonça, Tania Allard.

- The napari team: Juan Nunez-Iglesias, Grzegorz Bokota, Peter Sobolewski, Talley Lambert, to name a few!

- The CZI folks: Kyle I S Harrington, Ashley Anderson, Ziyang Liu, Jun Ni, Justine Larsen, Nicholas Sofroniew, among many more!

- Anaconda employees: Marco Esters, Paul Yim, Jannis Leidel.

- Spyder contributors: Ryan Clary, Carlos Córdoba, C.A.M Gerlach.

- MNE-Python maintainers: Richard Höchenberger, Eric Larson.