libsf_error_state: SciPy's first shared library

Published January 24, 2025

steppi

Albert Steppi

Introduction

This is the story of the first1 shared library to be shipped as part of SciPy. It offers a glimpse at some of the

complexity SciPy tries to hide from users, while previewing some exciting developments in

scipy.special.

Python has become wildly popular as a language for scientific and other data-intensive applications. It owes much of its success to an exemplary execution of the "compiled core, interpreted shell" principle. One can orchestrate simulation pipelines, preprocess and munge data, set up and use explanatory or predictive statistical models, make plots and tables, and more, in an expressive high level language — while delegating computationally intensive tasks to compiled libraries.

The default CPython interpreter was designed specifically to make it easy to extend Python programs with efficient native code. The Python C API is well thought out and straightforward to work with. The controversial global interpreter lock or GIL, a barrier to free threading within Python, has the benefit of making it much easier to call out to native code, since one need not worry about the thread-safety of wrapped compiled libraries.

By wrapping, filling in gaps, and providing user friendly Python APIs to a wide range of battle tested, permissively licensed and public domain scientific software tools — SciPy's founding developers2 were able to kickstart the growth of the Scientific Python ecosystem. There are now worlds of scientific and data intensive software available in Python. Users who spend their time in the interpreted shell may not be aware of the complexity that lies underneath. Journeying deeper into the stack, it can be surprising to see the level of work that can go into making even a relatively simple feature work smoothly.

Here, the simple feature in question is error handling for mathematical functions in scipy.special that operate

elementwise over NumPy arrays. Let's look into this more closely.

NumPy Universal functions

A NumPy ndarray represents an arbitrary

dimensional array of elements of the same data type, stored in a continguous buffer at the machine level. A universal

function or ufunc for short is a Python level function which

applies a transform to each element of an ndarray by looping and operating elementwise over the underlying contiguous

buffer in efficient native code.

Here's the ufunc np.sqrt in action:

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: A = np.arange(1, 11, dtype=float)In [3]: AOut [3]: array([ 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10.])In [4]: np.sqrt(A)Out [4]:array([1. , 1.41421356, 1.73205081, 2. , 2.23606798, 2.44948974, 2.64575131, 2.82842712, 3. , 3.16227766])

For large arrays, the speedup from applying np.sqrt over an ndarray rather than math.sqrt over each element of

a list is significant. On my laptop I witnessed:

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: A = np.arange(1, 1000000, dtype=float)In [3]: %timeit np.sqrt(A)1.35 ms ± 49 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1,000 loops each)In [4]: B = [float(t) for t in range(1, 1000000)]In [5]: %timeit [math.sqrt(t) for t in B]103 ms ± 1.18 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

Error handling

What should happen if one gives invalid input to a ufunc? If we pass a negative float to math.sqrt

a ValueError is raised.3

In [1]: import mathIn [2]: math.sqrt(-1.0)ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)Cell In[2], line 1p----> 1 math.sqrt(-1.0)ValueError: math domain error

What if one applies a ufunc over a large array and only a small number of inputs are invalid? Would it be reasonable to

raise a ValueError even though almost every calculation succeeded and produced a useful result? Fortunately, that's

not what happens:

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: A = np.arange(-1, 1000, dtype=float)In [3]: np.sqrt(A)<ipython-input-3-d44c5e97424e>:1: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in sqrt np.sqrt(A)Out[3]:array([ nan, 0. , 1. , ..., 31.57530681, 31.591138 , 31.60696126])

Instead a warning is raised and -1.0 is mapped to NaN, a special floating point

number representing an undefined result. NaNs propagate sanely through most calculations, making them useful in

such situations.

What if we want to suppress the warning? Perhaps we're applying a ufunc within an inner loop and getting buried in

unhelpful warning output. For such situations, NumPy provides an API for controlling floating point error

handling. Here's the

np.errstate context manager in

action:

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: A = np.arange(-1, 1000, dtype=float)In [3]: with np.errstate(invalid="ignore"): ...: B = np.sqrt(A) ...:In [4]: BOut [5]:array([ nan, 0. , 1. , ..., 31.57530681, 31.591138 , 31.60696126]

What if we genuinely want to raise if any kind of floating point error occurs? Perhaps negative inputs imply a sensor failure in a latency insensitive robot which will ping its handlers upon an exception and hibernate until it can be physically recovered.

np.errstate has us covered here too:

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: A = np.arange(-1, 1000, dtype=float)In [3]: with np.errstate(all="raise"): ...: B = np.sqrt(A) ...:---------------------------------------------------------------------------FloatingPointError Traceback (most recent call last)Cell In[3], line 2 1 with np.errstate(all="raise"):----> 2 B = np.sqrt(A)FloatingPointError: invalid value encountered in sqrt

scipy.special

NumPy has over 60 ufuncs available for a range

of mathematical functions and operations, but more specialized functions useful in the sciences and engineering are out

of scope. Ufuncs for over 230 such functions can be found instead in scipy.special.

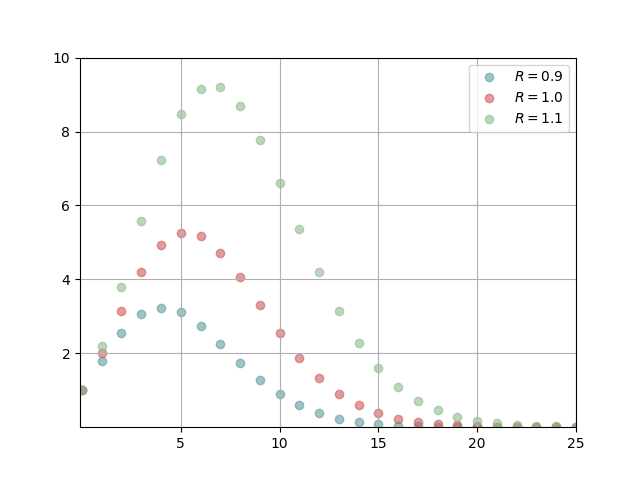

Just for fun, let's use scipy.special.gamma, which implements a continuous extension of the factorial function called

the Gamma function, to reproduce a plot from the Wikipedia article

"Volume of an n-ball". The plot shows how the volume of a solid

multi-dimensional sphere depends on the dimension n when the radius R is one of 0.9, 1.0, or 1.1.

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltimport numpy as npimport scipy.special as specialN = np.arange(0, 26) # dimensionR = np.array([0.9, 1.0, 1.1]) # radius# meshgrid makes it convenient to evaluate formula over the grid N x RN, R = np.meshgrid(N, R)# Formula for volume of an n-ball in terms of radius R and dimension N.V = np.pi**(N/2)/special.gamma(N/2 + 1) * R**Nfig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)ax.scatter(N[0], V[0], color='cadetblue', alpha=0.6, label="$R = 0.9$")ax.scatter(N[1], V[1], color='indianred', alpha=0.6, label="$R = 1.0$")ax.scatter(N[2], V[2], color='darkseagreen', alpha=0.6, label="$R = 1.1$")ax.set_xlim(0, 25)ax.set_ylim(0, 10)ax.set_xticks([5, 10, 15, 20, 25])ax.set_yticks([2, 4, 6, 8, 10])ax.grid()ax.legend()plt.show()

which outputs:

scipy.special error handling

What if one of the ufuncs in scipy.special recieves an array with some invalid elements? The Gamma function has

singularities at non-positive integers, similar to how 1 / x has a singularity at 0.

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: import scipy.special as specialIn [3]: x = np.array([-4., -2., 0., 2., 4.])In [4]: special.gamma(x)Out [4]: array([nan, nan, inf, 1., 6.])In [5]: with np.errstate(all="raise"): ...: _ = special.gamma(x) ...:In [6]:

np.errstate had no impact on error handling, there were no warnings, but we do see NaNs in the output.4 What's

going on? Well, NumPy's ufuncs are provided in a C extension

module that's part of NumPy. There's some C code in this extension

module for managing the state for error handling policies. The ufuncs in scipy.special come from a different extension

module in SciPy. Extension modules from separate projects are like separate worlds, and cannot communicate with one

another except through their Python interfaces. SciPy instead has its own context manager:

scipy.special.errstate that

mirrors np.errstate.

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: import scipy.special as specialIn [3]: x = np.linspace(-4, 4, 5)In [4]: with special.errstate(all="raise"): ...: _ = special.gamma(x) ...:---------------------------------------------------------------------------SpecialFunctionError Traceback (most recent call last)Cell In[4], line 2 1 with special.errstate(all="raise"):----> 2 _ = special.gamma(x)SpecialFunctionError: scipy.special/Gamma: singularity

Some exciting developments

To create a ufunc for a mathematical function, one needs a scalar implementation of this function, known as a scalar

kernel, that's written in a compiled language. Until recently, scipy.special had scalar kernels written in all of C,

C++, Fortran 77, and Cython. In August of 2023, Irwin Zaid (@izaid) at Oxford proposed

rewriting all of the scalar kernels in C++ header files in such a way that they could be included in both C++ and CUDA

programs. This would allow these scalar kernels to also be used in GPU-aware array libraries like CuPy and PyTorch,

improving special function support across array library backends. Over the past year, I've been working together with

Irwin to put this plan into action. With additional help from SciPy maintainer Ilhan Polat

(@ilayn), who made a heroic effort to translate over twenty thousand lines of Fortran scalar

kernel code to C, and contributions from other volunteers, substantial progress has been made. We're now in the process

of splitting these headers into a separate library called xsf. This is a story deserving of its own post. Until then,

see the first issue in the xsf repo for more info.

At the outset of this project, scipy.special had been under-maintained for several years. I'm not sure if there were

any active maintainers left who fully understood the details of the infrastucture scipy.special has been using for

creating ufuncs. However, it was to clear to everyone involved that this infrastructure was greatly complicated by the

need to work with scalar kernels from so many languages. Standardizing on C++ offered a chance to simplify things

considerably.

In the Spring of 2024, things moved fairly quickly because Irwin was able to put in time working on SciPy to help get

things off the ground. He found that the existing ufunc infrastructure was not flexible enough for work he had planned

involving Generalized universal functions

(gufuncs for short) so he wrote new machinery from scratch. Ufuncs and gufuncs created with the new machinery live in a

separate extension module from those created with the old machinery.5 It will be a great win in terms of simplifying

scipy.special's build process when all ufuncs can be moved over to the new infrastructure but in the short term there

was a problem.

Error handling redux

After splitting them between multiple extension modules, the error policy state could no longer be easily shared

between ufuncs. We noticed something was wrong due to a failure in a doctest for

special.seterr.

The expected error was not being raised.

Examples -------- >>> import scipy.special as sc >>> from pytest import raises >>> sc.gammaln(0) inf >>> olderr = sc.seterr(singular='raise') >>> with raises(sc.SpecialFunctionError): ... sc.gammaln(0) ... >>> _ = sc.seterr(**olderr)

special.gammaln was one of a handful of ufuncs moved to the new extension module.

Both extension modules contained a separate copy of the state for managing error handling policies, but the user facing

special.errstate could only see and change the state from the first extension module. While investigating, we also

found that, for some reason, there was a separate extension module just for the function special.ellip_harm_2. As

expected, special.errstate did not and had never worked for ellip_harm_2 either, but since there were no relevant

tests, no one knew.

We saw three options:

-

Have the Python interface for modifying the error handling state (

special.errstateandspecial.seterr) update the state in each extension module, taking care that the state remains synchronized. -

Extract the error handling state and primitives for managing it into a shared library that would be linked with each extension module.

-

Keep the error handling state in one of the extension modules and have it retrieved from there by the others.

We chose to create a shared library because it seemed like the more principled option. As the saying goes: we do these things not because they are easy, but because we thought they were going to be easy.6 Quansight Labs Co-director Ralf Gommers (@rgommers) knew from long experience that this may be difficult to get right, but trusted that we'd be able to figure it out.

Static vs dynamic linking

Before we continue, let's review some background information. Feel free to skim or skip this section if you know this stuff already.

Consider the structure of a C program. It must have one and only one file with an entry point function main where

execution begins. This file may refer to functions, global variables, and datatypes from other files. For a C program

with multiple files, each file is compiled separately into an object file of machine instructions, specific to a

particular platform, giving explicit commands directly to the CPU. A program called a linker is responsible for

combining the generated object files into a single program. A library is a collection of code containing functions and

datatypes which can be used in programs, but which itself doesn't have a main function.

There are two ways library code can be linked into a program. The simplest way is static linking, where the library code is bundled directly into the program. Two programs statically linked with the same library will each have their own separate copy of the library. Special function error handling broke because the code responsible for it was statically linked into each separate extension module. By contrast, when library code is dynamically linked, it is not included in the executable binary file for the program at compile time. It instead lives in a separate binary file, called a shared library, which can be loaded into the program at runtime.

In addition to executable machine instructions, each object file contains a symbol table mapping each identifier used in the original source file (e.g. a function name) to either the position in the executable code where the identifier is defined (e.g. the function's definition) or a placeholder if there's no definition in the source file. When combining object files into a single program through static linking, the linker fills these placeholders by searching the symbol tables of the other object files being linked into the program.

Object files from a statically linked library are treated no differently from object files generated from the program's source code. By contrast: for dynamic linking, at compile time, the linker only checks the shared library's symbol table for entries that could fill placeholders, but does not link the shared library into the program. Shared libraries are instead loaded by programs at runtime. Function names, variable names, and other identifiers a shared library makes available to programs are referred to as symbols exported by the library.

Some benefits of shared libraries are that:

- Separate programs can load and use the same library, rather than having separate copies bundled into each program, reducing code duplication.

- Updates can be made to a shared library without requiring dependent programs to be recompiled, so long as the library's interface doesn't change.

There are tradeoffs. A small amount of overhead may be added to function calls, since the process of function lookups is more involved, and the need to locate and load the shared libray into memory at runtime can incur a fixed amount of startup overhead.

Sharing global state

Shared libraries cannot share global state between programs running in separate processes. Each process has its own separate address space of memory it can access, and interprocess communication requires special protocols. Nevertheless, a shared library can be used to share global state between separate Python extension modules that were dynamically loaded by a Python interpreter running in the same process, since only a single copy of the library is loaded into memory.

Note that the title of this article isn't entirely accurate. A Python extension module is itself a shared library which is loaded by the Python interpreter at runtime. Thus SciPy actually contains many shared libraries and has done so from its earliest days. What we mean is the first regular shared library that's not a Python extension module. Also, although we've been talking in terms of linking programs with a shared library, in this case we are linking Python extension modules with a shared library. It's perfectly valid to link one shared library with one or more others.

The relevant code

Having decided on the shared library approach, we looked into code scipy.special used for managing error handling state.

In essence, things were very simple. Let's walk through the core lines.7

There is an enumeration type sf_action_t giving human readable names to the different error handling policies:

enum sf_action_t { SF_ERROR_IGNORE = 0; SF_ERROR_WARN; SF_ERROR_RAISE;}

And then an array sf_error_actions storing the error handling policy associated to each special function error

handling type. We see that the default is to ignore all errors, matching what we observed in the example with

special.gamma.

static sf_action_t sf_error_actions[] = { SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_OK */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_SINGULAR */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_UNDERFLOW */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_OVERFLOW */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_SLOW */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_LOSS */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_NO_RESULT */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_DOMAIN */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_ARG */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE, /* SF_ERROR_OTHER */ SF_ERROR_IGNORE /* SF_ERROR__LAST */};

To make the correspondence between entries in the array and special function error handling types clear, there is

another enumeration type, sf_error_t, which associates the name for each error type with the corresponding index into

sf_error_actions.

typedef enum { SF_ERROR_OK = 0, /* no error */ SF_ERROR_SINGULAR, /* singularity encountered */ SF_ERROR_UNDERFLOW, /* floating point underflow */ SF_ERROR_OVERFLOW, /* floating point overflow */ SF_ERROR_SLOW, /* too many iterations required */ SF_ERROR_LOSS, /* loss of precision */ SF_ERROR_NO_RESULT, /* no result obtained */ SF_ERROR_DOMAIN, /* out of domain */ SF_ERROR_ARG, /* invalid input parameter */ SF_ERROR_OTHER, /* unclassified error */ SF_ERROR__LAST} sf_error_t;

sf_action_t is declared static to make use of its name local only to the file where it's defined. To work with this

array externally, there are two functions, scipy_sf_error_set_action for updating and scipy_sf_error_get_action for

querying the error handling policy associated to a given error type.

void scipy_sf_error_set_action(sf_error_t code, sf_action_t action){ sf_error_actions[(int)code] = action;}sf_action_t scipy_sf_error_get_action(sf_error_t code){ return sf_error_actions[(int)code];}

Using the terminology from before, these are the symbols that we want to export from the shared library.

If a user runs the following in an IPython session

In [1]: import scipy.special as specialIn [2]: special.seterr(loss="warn")

then somewhere down in the stack, the following call will occur to update the error state.

scipy_sf_error_set_action(SF_ERROR_LOSS, SF_ERROR_WARN)

If special.gamma is evaluated at an array containing a negative integer, then when the scalar kernel is called on the

offending entry, it will signal SF_ERROR_SINGULAR and sf_error_actions will be consulted to figure out what action

to take.

The many battles to actually ship it

The shared library libsf_error_state's contents are fairly simple, but how does one actually ship a shared library

within a Python package like SciPy? When we started out, we weren't even aware of any Python packages that contain an

internal shared library. The process for creating and using shared libraries depends on the operating system and

compiler toolchain. SciPy supports a wide range of platforms in aim of its goal to democratize access to scientific

computing tools; the greatest challenge turned out to be getting things to work on each of them. Several times, just

as we thought everything was finally working, another quirk would pop up that needed to be addressed.

Path troubles

The initial challenge was finding the right invocations to give to the Meson build system

used by SciPy.8 Extension modules are configured in the meson.build files spread across SciPy's source tree and we

needed to figure out how to set up a shared library and link it into each of the special function ufunc extension

modules. Irwin and I begin working on this independently, comparing notes as we went.

The first hiccup is that the following invocations were working on Irwin's Mac.

Setting up the shared library like this.

sf_error_state_lib = shared_library('sf_error_state', # Name of the library # Implementation files contained it. ['sf_error_state.c'], # Additional places the preprocessor can look for header files include_directories: ['../_lib', '../_build_utils/src'], install: true)

and adding a link_with entry to the creation of each extension module:

py3.extension_module('_special_ufuncs', ['_special_ufuncs.cpp', '_special_ufuncs_docs.cpp', 'sf_error.cc'], include_directories: ['../_lib', '../_build_utils/src'], dependencies: [np_dep], link_with: [sf_error_state_lib], # The new line link_args: version_link_args, install: true, cpp_args: ['-DSP_SPECFUN_ERROR'], subdir: 'scipy/special')

However, on my Linux machine SciPy would build without issue, but attempting to import scipy.special would

result in the error:

ImportError: libsf_error_state.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

After a period of head scratching in which I pondered every possible explanation except the correct one, I showed Irwin

what I tried and the error message I was getting. It turned out that the difference in operating systems was a red

herring. The issue was that, of the two methods for building SciPy from source for development recommended in SciPy's

contributor

documentation, I was

using the "python dev.py build" workflow and he was using an editable install: "pip install -e . --no-build-isolation".

For the editable install, SciPy is installed directly in its own project folder, and the shared library and the relevant

extension modules were all being installed next to each other in ~/scipy/scipy/special. For the dev.py workflow,

SciPy is installed elsewhere. Since I didn't specify where to install the shared library, it got put in the wrong

place. I fixed things by directly configuring the install_dir in Meson like this:

sf_error_state_lib = shared_library('sf_error_state', # Name of the library # Implementation files contained it. ['sf_error_state.c'], # Additional places the preprocessor can look for header files include_directories: ['../_lib', '../_build_utils/src'], install: true # Tell meson where to install the shared library install_dir: py3.get_install_dir() / 'scipy/special',)

Even after this, I was still seeing the same error. I asked Ralf about it, and found what happens is that pip

goes through meson-python and pip's editable install support uses

extension modules straight from the build directory, while dev.py uses Meson directly and does an actual install

step with meson install. For the editable install, two things allow loading the shared library to work with the above Meson config:

(1) Meson adds the build directory to the RPATH of each extension module in

order to enable usage without an install step but strips it again during the meson install step used in the dev.py build, and (2) when

the install_dir for a shared library is outside of the Python package's tree under site-packages,

meson-python takes care of rewriting the install dir automatically to be within site-packages and it rewrites

the RPATHs to match. The dev.py method doesn't include either of these fixes, and as a result, the RPATH that tells the dynamic linker where to look for shared libraries ends up being wrong.

To get things to work with dev.py, I needed to explicitly set the RPATH in Meson by adding install_rpath:'$ORIGIN'

to each extension module. '$ORIGIN' in this case means to search in the same folder as the extension module.

Building Wheels on Windows

After setting install_dir and install_rpath correctly, all but one of SciPy's CI jobs were passing. The sole failing

job involved building a wheel on Windows. A

wheel can be thought of as a

precompiled binary for a Python package. The underlying issue was that Windows does not have support for something like

RPATH, following instead a less configurable set of rules

for determining the search path for shared libraries.

It took us a day of work to get to this point. Since things were not as straightforward as expected; I took it from here.

At the time I didn't really have any experience developing for Windows and didn't even have a Windows machine available at home to use. I looked up how to run Windows in a VM and got to work.

I found a solution using delvewheel, a tool for bundling shared libraries

into wheels on Windows. It worked on my machine but

wasn't viable for production. Fortunately,

Ralf had seen this problem before and had a ready made solution: manually loading the shared library from within

scipy/special/__init__.py so it would be available when needed:

def _load_libsf_error_state(): """Load libsf_error_state.dll shared library on Windows libsf_error_state manages shared state used by ``scipy.special.seterr`` and ``scipy.special.geterr`` so that these can work consistently between special functions provided by different extension modules. This shared library is installed in scipy/special alongside this __init__.py file. Due to lack of rpath support, Windows cannot find shared libraries installed within wheels. To circumvent this, we pre-load ``lib_sf_error_state.dll`` when on Windows. The logic for this function was borrowed from the function ``make_init`` in `scipy/tools/openblas_support.py`: https://github.com/scipy/scipy/blob/bb92c8014e21052e7dde67a76b28214dd1dcb94a/tools/openblas_support.py#L239-L274 """ # noqa: E501 if os.name == "nt": try: from ctypes import WinDLL basedir = os.path.dirname(__file__) except: # noqa: E722 pass else: dll_path = os.path.join(basedir, "libsf_error_state.dll") if os.path.exists(dll_path): WinDLL(dll_path)_load_libsf_error_state()

One week in, all CI jobs were passing and the PR creating

libsf_error_state was merged. We did it! We fixed the bug we'd introduced in special.errstate with months to go

before the next SciPy release — or so we thought.

Breaking SciPy for MSVC builds

On May 30th, SciPy maintainer and conda-forge core member @h-vetinari posted a comment on his open PR, scipy-feedstock/gh-277. The first release candidate for SciPy 1.14.0 had just come out, he was starting the process to add version 1.14.0 to Conda-Forge, and noticed that Windows builds for SciPy 1.14.0 were failing with the following error:

lld-link: error: undefined symbol: scipy_sf_error_get_action

How could this be? SciPy's own CI jobs were passing on Windows, but here, symbols from lib_sf_error_state were clearly

not being found. The thing is, at that point in time there was still a key gap in SciPy's CI coverage. Although there

were Windows builds in CI, they all used the MinGW compiler toolchain. There were no jobs using

MSVC or Clang-cl,

a Clang compiler driver that aims for compatability with MSVC. Clang-cl is used for Windows builds in conda-forge and we had run into

another platform specific difference.

Fortunately, h-vetinari knew what the problem was. On Linux, macOS (and Windows while using MinGW), symbols from shared

libraries are exported by default, but on Windows with MSVC or Clang-cl they must be explicitly exported from shared

libraries and explicitly imported into consumers by annotating source code with special compiler directives:

__declspec(dllexport)

for exports and

__declspec(dllimport)

for imports.

He had a recipe ready to use: defining and using macros which conditionally compiled to the right thing depending on their context.

// SCIPY_DLL// inspired by https://github.com/abseil/abseil-cpp/blob/20240116.2/absl/base/config.h#L736-L753//// When building sf_error_state as a DLL, this macro expands to `__declspec(dllexport)`// so we can annotate symbols appropriately as being exported. When used in// headers consuming a DLL, this macro expands to `__declspec(dllimport)` so// that consumers know the symbol is defined inside the DLL. In all other cases,// the macro expands to nothing.// Note: SCIPY_DLL_{EX,IM}PORTS are set in scipy/special/meson.build#if defined(SCIPY_DLL_EXPORTS) #define SCIPY_DLL __declspec(dllexport)#elif defined(SCIPY_DLL_IMPORTS) #define SCIPY_DLL __declspec(dllimport)#else #define SCIPY_DLL#endif

As soon as I had a chance, I fired up a Windows VM again and put together a PR implementing h-vetinari's solution. After a couple missteps, Clang-cl builds were working again. There would be no need to push back the release date. A couple weeks later, fellow Quansight Labs member and LFortran/LPython core developer Gagandeep Singh (@czgdp1807) submitted a PR to plug the gap in SciPy's CI coverage.

Thread safety

In the introduction I'd mentioned that CPython's GIL makes it easier to extend Python with C or other compiled languages since one doesn't need to worry about the thread safety of wrapped code. Still, having only one thread in a running Python process able to execute Python code at a time is a severe limitation for multicore applications. In October 2023, a Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP) was accepted to make the GIL optional. This proposal, PEP 703, is well worth reading for its thoughtful summary of the surrounding issues. CPython 3.13 launched with an optional free-threaded mode which supports running with the GIL disabled. Free-threading in Python offers great promise, but to take advantage of it, extensions need to be rewritten with thread safety in mind.

libsf_error_state is obviously not thread safe. There is a global array carrying the current state of special

function error handling policies with nothing to stop competing threads from trying to access the same memory

location. Simultaneous modifications could even leave an entry in some corrupt and indeterminate state. This situation

is known as a data race and leads to

undefined behavior in C and C++. Weird things can happen when there

is a data race.

The latest tale in the saga of libsf_error_state is a PR from Edgar

Margffoy (@andfoy) — a member of Quansight Labs'

free-threaded Python team — to ensure

thread safety by declaring the array sf_error_actions thread local. This eliminates the data-race by making it so each

thread gets its own separate copy of the array. Edgar and the others on the free-threaded Python team have been doing

great work improving support for free-threaded Python across the ecosystem for much of the past year.

In a curious reversal, it is now (the win32 flavor of) MinGW that is causing trouble due to lack of support for

thread local variables.

Reflections

Now that the dust has mostly settled, it's valuable to look back and try to judge whether we made the right choice. Over

the entire timeframe, the primary goal for Irwin and I was always to make as much of SciPy special available on the GPU as

possible, with secondary goals of simplifying SciPy special's build process and improving the scalar kernel codebase. The

story of libsf_error_state is that of a side quest — a story of needing to fix something we broke in pursuit of bigger

things — and the challenges we faced and brought to others because we underestimated the difficulty of our chosen

solution. Having a single array for managing shared state between the extension modules appeals to a desire to have a

single source of truth, but looking back, it would have taken much less time to have each extension module carry its

own copy of the array, and to always update them all together.

While conducting research for this blog post, I discovered another wrinkle. Just beneath our noses, there was another

extension module, _ufuncs_cxx for

scalar kernels written in C++. Through the byzantine machinations of SciPy special's build system, brought about by

the need to handle scalar kernels written in 4 languages, the actual ufuncs from _ufuncs_cxx are defined in the

_ufuncs extension module discussed earlier. Because special.errstate worked without issue for these ufuncs, and

they appeared to be coming from the _ufuncs extension module, I never looked more deeply into _ufuncs_cxx. It

turns out that _ufuncs_cxx has its own copy of sf_error_actions and it is updated in synchrony when setting the

error state from Python.

From github.com/scipy/.../_ufuncs_extra_code.pxi:

for error, action in kwargs.items(): action = _sf_error_action_map[action] code = _sf_error_code_map[error] _set_action(code, action) scipy.special._ufuncs_cxx._set_action(code, action)

I also found an October 2016 comment on GitHub from

currently inactive SciPy maintainer Josh Wilson (@person142), the original author of

SciPy special's error handling features, which shows he was already aware of the problem we ended up facing. He was

trying to make special function error handling work correctly in

scipy.special.cython_special, a module for

calling scalar versions of special function from Cython. To quote:

"To make the necessary modifications to cython_special error handling we need to instead share a single global variable between the two extension modules. On gcc we could do this with -rpath, but coming up with a portable solution seems messy. Is there a nice way out of this?"

A nice way? Perhaps not. He wisely chose instead to disable error handling in cython_special entirely. But maybe now

that we at least have a portable way to share global state between extension modules, this is worth revisiting.

Before we finish, one more gem: in another GitHub comment from

2016, currently inactive SciPy BDFL Pauli Virtanen

(@pv) suggested to "make sf_error error handling thread-local (which probably should be done

in any case)". Over eight years later this is finally happening. I should probably go back and read old comment threads

more often.

Funding acknowledgements

This work was supported by the 2020 NASA ROSES grant, Reinforcing the Foundations of Scientific Python.

Footnotes

-

The first regular shared library that's part of SciPy itself, not including Python extension modules within SciPy or shared libraries shipped alongside SciPy in platform specific wheels to supply dependencies which may not be consistently available otherwise. ↩

-

Travis Oliphant, Pearu Peterson, and Eric Jones. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SciPy#History) ↩

-

Having

math.sqrt(-1.0)evaluate to the complex number1jinstead of raising would violate a principle that the output type should depend only on the input type, not the input value. Allowing the latter makes code more difficult to reason about, both for programmers and for tools like static type checkers and jit compilers. ↩ -

Those using

scipy<1.15will seeinfinstead ofnanat negative integers due to a bug inspecial.gammawhich was fixed in the PR scipy/#21827.If you're curious whyspecial.gamma(0.)evaluated to+inf, note that the IEE-754 floating point standard requires signed zeros-0.and+0..special.gamma(-0.)andspecial.gamma(+0.)evaluate the limit of the Gamma function asxapproaches0from the left and right respectively. ↩ -

We could have stuck to one extension module by making it more complicated, but the idea was to build the simpler extension module that would be possible after all scalar kernels are written in C++ headers, move ufuncs over to it incrementally, and then remove the old extension module after this process is completed. ↩

-

The Programmers Credo. From a 2016 twitter post by Maciej Cegłowski. ↩

-

Some small simplifications have been made to keep the explanations concise. To see the library files as they exist at the moment I'm writing this, see the the following GitHub permalinks for scipy/special/sf_error_state.c and the corresponding header scipy/special/sf_error_state.h. ↩

-

For more info on SciPy's move to Meson, see Ralf's 2021 Quansight blog post ↩